|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

While conducting research on the many interesting fossil plant localities in Northern California, I happened to read about an especially promising site in the fabulous Gold Rush Country, western foothills of the Sierra Nevada--the Chalk Bluff area, a number of miles from Grass Valley/Nevada City (they are contiguous communities in Nevada County). The Chalk Bluff region was the scene of extensive hydraulic gold recovery operations during the mid to late 1800s, a historic period when miners extracted millions of dollars' worth of gold (mostly at the old price of around 20 dollars per ounce) from the widely exposed auriferous gravels of the northern Mother Lode. In California, hydraulic mining initially began on a small scale in 1852, but soon developed into a regionally ubiquitous, sophisticated method of working great volumes of gold-bearing gravels. The basic idea was to aim high-powered jets of water through huge nozzles at the auriferous gravels, washing away tons upon tons of debris, after which the gold-bearing debris/sludge traveled through a deep cut or tunnel that was lined with a series of sluices to capture the gold. During roughly a 30-year period, from 1855 to 1884, hydraulic miners washed away approximately 250 million cubic yards of material. This created repeated catastrophic flooding of farmlands and valuable property in the flatlands below the hydraulic operations. Eventually, a farmer in Marysville by the name of Woodruff decided to sue the North Bloomfield Gravel Mining Company to prevent further debris from being discharged into the Yuba River. That case was presided over by Judge Lorenzo Sawyer, who issued his famous "Sawyer Decision" in January of 1884--a 225-page document that with effective legal decree abolished large-scale hydraulic operations in California for all time. During the decades of gold extraction, the hydraulickers at Chalk Bluff incidentally exposed a wonderful fossil plant-bearing horizon interbedded with the auriferous gravel deposited by the Tertiary Yuba River (sedimentary accumulations usually considered a proximal correlative stratigraphic manifestation of the distal Eocene Ione Formation, whose type locality lies in the vicinity of Ione, Amador County, western foothills of the Sierra Nevada, about 62 miles southwest), a relatively narrow zone of fine-grained clays, usually not more than 3 feet thick, situated within the roughly 400 feet of pebble-cobble gold-bearing gravels of early middle to middle Eocene geologic age, some 48 to 45 million years old. This fossilferous bed of claystone--typically referred to as "chocolate shales" for their memorable coloration upon fresh exposure--contains the remains of numerous species of ancient botanic specimens: leaves and seeds and pollens and flowering structures, whose preservation is often magnificent. Sometimes the leaves reveal beautiful examples of the original cuticle, which is that thin wax coating on the upper epidermis of leaves that helps protect against excessive water loss, mechanical injury, and fungal attack. In the middle Eocene chocolate shales, exposed by hydraulicking methods during gold recovery, the original cuticle is locally quite common, appearing as a thin wax paper-like material that easily peels off the matrix upon direct exposure to the air; for this reason, paleobotanists wrap it in tissue paper with urgent immediacy to prevent any loss of the invaluable substance--a genuine rarity in the fossil record. In addition to the fossil leaves, relatively common pieces of petrified wood can also be observed in the same general area, mainly from a gravelly channel a few feet below the leaf-bearing chocolate shales. My personal research disclosed rather quickly that the Chalk Bluff region is frequently mentioned in the paleobotanical literature on the fossil floras of Northern California. It is in fact a renowned fossil-bearing district, among the first plant-yielding areas scientifically studied in California after hydraulic operations had exposed the leaf-petrified wood deposit in the mid 1800s. Indeed, the history of paleobotanical and geological investigations pertaining to Chalk Bluff is quite extensive. A professor Josiah Dwight Whitney first mentioned the Chalk Bluff fossils in an article published in the first volume of Geology, early 1870s. They were later described in detail in a truly remarkable paper, Report of the Fossil Plants of the Auriferous Gravel Deposits of the Sierra Nevada by Leo Lesquereux, Memoirs of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard College, Volume 5, Number 2, 1878. Prior to the advent of cyber-technology (AKA, the Internet), where even the most obscure scientific papers can often be accessed online, I was fortunate to locate an original copy of Lesquereux's classic monograph at the library of the California Division of Mines and Geology in Pleasant Hill. Lesquereux includes numerous detailed line drawings of the fossil leaf specimens--a feature usually inferior to photographs, but in this example the scholarly drawings definitely enhance the quality of the finished product. In 1880, professor Whitney discusses the Chalk Bluff area once again in his monumental publication The Auriferous Gravels of the Sierra Nevada, California, Vol. 1, Memoirs of the Museum of Comparative Anatomy at Cambridge, Massechesetts. In 1911, geologist Weldemar Lindgren published the definitive statement on the gold-bearing gravels of the northern Sierra Nevada: United States Geological Survey Professional Paper 73, The Tertiary Gravels of the Sierra Nevada of California. For a section of the volume entitled Tertiary Fossil Plants, Lindgren solicited a report from then leading paleobotanist F. H. Knowlton, who mentions the Chalk Bluff site, along with 12 additional plant-bearing localities in northern California, including: Washington Gravel Mine, Independence Hill near Iowa City in Placer County; Volcano Hill, Placer County; Monte Cristo Gravel Mine, "summit of Spanish Peak in Plumas County;" Mohawk Valley, Plumas County; Bowens Tunnel, along the North Fork of Oregon Creek near Forest City in Sierra County; "about seven and a half miles southwest of Susanville, Lassen County;" Table Mountain, Tuolumne County; the north end of Mountain Meadow, Lassen County; and "near Moolight," Lassen County. In her 1935 report on a fossil leaf deposit in Plumas County, Northern California, Susan S. Potbury wrote that H. D. MacGinitie was, at that date, revising the Chalk Bluffs Flora, the results to appear in a forthcoming paleobotanical monograph. MacGinitie finally published his findings in 1941 in Carnegie Institute of Washington Publication 534, A Middle Eocene Flora from the Central Sierra Nevada. This is certainly the best study of the Chalk Bluffs Flora. "Mac" (an endearing moniker, given to him by contemporary professional paleobotany acquaintances) concluded that the Chalk Bluffs Flora could be assigned stratigraphically to the "Capay Stage" of the Eocene (named after the marine Capay Formation)--then understood as middle Eocene in geologic age--around 48 to 45 million years old--an interval that geologists currently correlate with the coal-bearing Domengine Formation exposed in the East San Francisco Bay area. Of course, based on several independent lines of scientific evidence, Capay-age now refers to rocks of late early Eocene times. Still and all, "Mac" got it right. The refined stratigraphic calibration of the "Capay Stage" is presently established at 52 to 50 million years old, which is not the geologic age of the younger Chalk Bluffs Flora (48 to 45 million years) that "Mac" had in mind. In 1974, the United States Geological Survey issued USGS Professional Paper 772 by Warren E. Yeend--Gold-Bearing Gravel of the Ancestral Yuba River, Sierra Nevada. Geologist Yeend mentions the Chalk Bluffs Flora in connection with a detailed discussion of the auiferous gravels, suggesting that the lowermost gold-bearing gravels near metamorphic Sierran bedrock, well below (older) than the leaf-bearing section, could actually be as old as Paleocene. As can best be determined, the Chalk Bluff leaf-bearing site is far from under-reported. It has been quite well known to amateur paleobotany enthusiasts since the 1860s, and several scientists have also spent considerable time investigating the fossil occurrence. As a matter of fact, the Chalk Bluff leaves that Leo Lesquereux first examined in the 1870s had been collected in the late 1860s by Charles D. Voy, an acclaimed naturalist and indefatigable gatherer of South Sea Islands ethnological items. So imagine my frustration when I could not find in any of the listed references a single explicit description of the exact geographic position of the Chalk Bluff region. The most promising lead came from a generalized map of the Northern Mother Lode contained in the volume, Geologic History of the Feather River Country, California, by Cordell Durrell, 1987. Durrell's map placed Chalk Bluff somewhere between Nevada City and Colfax in Nevada County--a decent start, I'll admit--but the map lacked important side-roads leading directly to the area. Now, normally, I'm not inclined to head off on a paleontology excursion without a full complement of accurate field information. But in this instance I was pretty much forced to do just that. If I was going to find the reportedly magnificent Chalk Bluff fossil field, I would necessarily need to head in to the hills impoverished in supporting directions data. My plan of attack was pretty straightforward. I'd simply follow Interstate 80 east out of the Sacramento area (at that date, I had fortuitously been visiting Northern California on personal business unrelated to matters paleontological), then turn north at the first major road in Colfax, about 46 miles distant in the direction of Reno, Nevada. Along the way toward Nevada City from Colfax, I'd decided to strike out east at approximately the "correct" distance north of Colfax--all of this itinerary, mind you, dictated to me by that generalized map included in Cordell Durell's publication. The plan was admittedly a long shot. I couldn't be sure I'd be able to recognize the Chalk Bluff region even if I were actually right on top of it. Additionally complicating the situation was that, based on previous journeys into that portion of the Gold Rush Country, I already understood that innumerable side roads presented a bewildering maze of routes that led to isolated communities and recent real estate developments--all part of the burgeoning populations of Nevada and Placer counties. So, which path to take to the fossils? My general idea, of course, was to watch for telltale evidence of hydraulic mining; the middle Eocene fossil plants were associated with auriferous gravels exploited by open pit hydraulic methods during the mid to late 1800s. But unless I could happily choose the correct route right off, I might travel far afield of my destination, losing precious time that could have been devoted to paleobotanical explorations. For this reason--and, simply because I had the hankering for it--I had decided to tote along a gold pan I'd borrowed from an acquaintance, in addition to my usual store of paleontological equipment. If I couldn't locate the Chalk Bluff fossil plant horizons within a decent amount of time, I figured I'd spend the remainder of my allotted day's adventures panning for gold along the famous Bear River, a known gold-producer of the 1800s. As a matter of fact, the so-called Colfax Quadrangle (within which Chalk Bluff and Bear River reside) yielded many millions of dollars' worth of gold during the Gold Rush delirium days, albeit the vast majority came from the hydraulic operations at Chalk Bluff. By the time I made Auburn (33 miles east of Sacramento) in the early morning hours of a potentially blistering summer's day down in the Great Central Valley, I was ready for some breakfast--a propitious decision as it turned out. Maybe it was the strong bracing coffee, or perhaps the energizing nourishment provided by the bacon and eggs and biscuits but suddenly I began to think more clearly on my day's adventures. While gazing out the window of that coffee shop on the striking mixed conifer/oak woodland scenery of the western Sierran foothills, I happily concluded that I was not necessarily compelled to resort to luck in order to locate the Chalk Bluff fossil plant bonanza. What if I could obtain a map of Nevada County? And what if that map showed the exact location of Chalk Bluff? This idea was definitely worth a try, I decided. At the grocery store across the street I found a road atlas of California. So far, so good, I thought. The publication I'd come across had a positive reputation for reliability. Immediately I turned to Nevada County and scanned the page for any kind of conceivable clue--and then, there it was right before my eyes--all the information I needed to find Chalk Bluff. I purchased that road atlas on the spot, and the rest as they say is history. It's probably problematic whether I would have been able to locate Chalk Buff without the aid of that road atlas, but at least I'm comforted to realize that I intuitively had the correct idea: Head north out of Colfax along the first major road I came to. Speaking of Colfax. Here's a geological aside to keep in mind: If you travel about 9 miles further on up the freeway from Colfax (roughly a mile past the Gold Run rest stop), you'll encounter along the north (left) side of I-80 one of the most accessible and extensive sections of unexploited middle Eocene auriferous gravels yet remaining in all of Northern California; it's the spectacular roadcut that extends roughly a half mile along I-80, a cut that gives travelers a wonderful opportunity to view up close and personal, from a moving vehicle, the excellently preserved fossil thalwegs of a river that dropped unimaginable fortunes in gold. A few miles north of Colfax, by the way, one crosses the Bear River. It was here that I decided to try my hand at a little gold panning during that initial visit to Chalk Bluff. On my return from the fossil plant horizon, I must have spent the better part of a couple of hours with bare feet in the Bear, rear on the bank and nose to the water, peering intently into the swirling material in my pan--all to no avail, ultimately. That golden gleam eluded my sight, although I'm not in the least surprised. My gold panning technique is far from efficient. Perhaps this has to do with a woeful lack of practice, because it's not that I haven't tried to improve my gold recovery method. I once had a certified gold panning expert try to improve my ways. He repetitively dropped two or three pieces of lead shot into my successive pans of experimental gravel, then instructed me to recover those pieces by slowly and surely concentrating the "fines' of my dirt with waters supplied by a mountain stream. After I'd cost him a small fortune in lead, he concluded with high confidence that I'd likely become prolifically rich someday, as he was certain that I would have no trouble finding gold nuggets no smaller than a cannonball. During that first visit to the Chalks Bluffs Flora deposit, I continued to follow the road atlas with faithful fidelity, managing to arrive at the great abandoned hydraulic pit in good order, with plenty of time available not only for fossil prospecting, but general geologizing, as well. As I quickly ascertained through reconnaissance, getting up to paleontological speed as it were, the fossil leaves and petrified wood occur to the immediate north and south of the primary dirt path through the middle Eocene auriferous gravels exposed by hydraulic gold miners during the mid to late 1800s. I also noted, upon subsequent visits undertaken not a few years later, that one needs to watch carefully for No Trespassing signs here. Most of this area remains in private ownership, where explicit advance permission from the property owners must be secured prior to fossil hunting. And even if you don't observe obvious posted documentation of private property--never assume that one is allowed to step anywhere off the main road within the Chalk Bluff hydraulic mining region without advance approval. Always conduct preliminary due diligence: Contact officials with the local United States Forest Service office to determine the most up-to-date rules and regulations regarding fossil collecting at Chalk Bluff. As you look to the north at the main Chalk Bluff fossiliferous sector, you will observe a broad ravine directly before you. Fossil leaves, seeds, flowering structures, and pollens occur in the pale brown-weathering shales near the base of the south side of that steep ravine--in other words, directly below your feet. When freshly exposed by hand excavation, the drab fossil-yielding shales instantly transform into a rich chocolate brown coloration--hence, their popular informal name "chocolate shales." But before you begin to hunt for fossils along that northern side, step across the road and take in the vista that spreads to the south. Here you will observe great chasms sliced through the gold-bearing gravels--acre after acre of water-blasted land that yielded unfathomable fortunes in gold. And now, only if unambiguous permission is still granted to collect here, proceed to find your way to the bottom of that ravine along the north side of the dirt road. From that top-side vantage point, though, there appears to be no easy route to reach the fossil-bearing area. Most of this north-facing wall is way too steep to try to descend safely. It was exposed by the gold seeking hydraulickers of the mid to late 1800s when they laid bare mile after mile of the auriferous gravel throughout the northern Mother Lode Country. During my first visit to Chalk Bluff, I was so exhilarated about having reached the right area that I impatiently scrambled down the south side of that ravine, dangerously sliding most of the way. Subsequent visits proved that this method was not only unesthetic, but needlessly reckless as well. A much safer path to the bottom exists a short way west of a convenient parking area, where the slopes remain far less precipitous and treacherous. Once at the base of the hydraulic cut, watch carefully for the fine-grained fossiliferous layer of chocolate-colored material, the so-called chocolate shales. Although this horizon is relatively narrow within the exposed sedimentary section--it is only three feet thick at most (and often partially masked by eroding overburden)--the leaf-bearing rocks are so different in lithology from the reddish brown pebble-cobble saturated auriferous gravel that you should have little difficulty identifying it in the field. If in doubt, give any potential fossil-bearing strata a whack or two with a geology hammer, exposing fresh rock. The leaf-yielding claystone is so fossiliferous that almost any chunk exposed will reveal at least a few 48 to 45 million year-old plant remains on the surface. The lithology of the fine-grained claystone, in combination with the abundance of fossil plants preserved within, provides persuasive evidence that the fossiliferous zone accumulated in stagnant oxbow lakes along the floodplains of Eocene-age aggrading rivers (watercourses that built up sediments, instead of downcutting their channels) that dropped great quantities of gold derived from now long-eroded lode veins in igneous rocks. And make no mistake about it. This claystone horizon in the middle Eocene auriferous gravel is often amazingly fossiliferous; the carbonized leaf impressions frequently lie plastered across the bedding planes, crisscrossing in a fascinating design of exceptional preservation (so-called "leaf litter"). The fossil-bearing layer of "chocolate shales" occurs in the coarse gravels that lie stratigraphically above the older "inner channel," a relatively narrow zone only about 40 feet deep (on average) and tens of feet wide, situated near bedrock, within which the vast majority of the abundant gold recovered by hydraulic methods was concentrated. Above the inner channel, or "blue ground" as the miners referred to this unbelievably rich zone, the younger gravels accumulated to a thickness of approximately 400 feet. These "bench gravels" contained much lower concentrations of gold, although a few reported localities in the younger auriferous gravels did indeed yield prolific quantities of the precious metal. Of course, the popular term "auriferous gravel" is not a formally accepted geologic formation name. It has no strict nomenclatural significance because there are other gold-bearing gravels in California of different ages. But, through long usage and tacit acceptance by local California geologists, the phrase has come to connote a very specific rock deposit. The auriferous gravels accumulated approximately 48 to 38 million years ago during the Eocene Epoch of the Cenozoic Era, an epoch technically calibrated at 56 to 33.9 million years ago. Based on the traditional interpretation of the geologic evidence, the gravels were deposited along the flood plains of aggrading rivers (most famously, the Tertiary Yuba River)--that is, watercourses which were building up sediments instead of eroding their channels. One of the great mysteries confronting geologists who've studied the auriferous gravel is why rivers that for millions of years were eroding their channels would suddenly begin to aggrade, or build up sediments. Several explanations have been considered to account for this occurrence, but only a select few competing plausible models appear to offer possibilities to fulfill the equation, answer all the questions. In his classic work Geologic History of the Feather River Country, geologist Cordell Durrell suggested that a prolonged change of climate from one of regular wet-and-dry seasons to one of irregular wet-and-wetter cycles may have triggered repeated episodes of catastrophic flooding, much like that which occurs in the vicinity of Rio De Janeiro, Brazil, a region with a climate and vegetation similar to that inferred for the Sierra Nevada area some 48 to 45 million years ago; such floods are very local, of course, but Durrell pointed out that no single flood need cover a large area to account for the accumulation of auriferous gravel. All that was needed was to have a sufficient number of flooding episodes within every part of the region where auriferous gravels now occur--in other words, the 10 northern counties of the Sierra Nevada, or an area of roughly 12,000 square miles. At first, this might seem to represent a prohibitively extensive area for floods to affect. But consider Durrel's calculations. Deposition of the auriferous gravel probably lasted for as long as 10 million years, or all of the middle Eocene. Therefore, there was ample time for periodic flooding to account for the gold-bearing gravels. Durrell suggested that if only one consequential flood occurred every 50 years, there could have been as many as 200,000 floods. If the rain gods were more generous and the figure was closer to one flood every 20 years, then the total climbs to a possible 500,000 floods. Now, Durrell introduces us to some basic arithmetic. Suppose each flood deposited an average of only two feet of sediment affecting an area of 10 square miles (a conservative figure completely within reason). That would mean that it would require 250,000 floods to bury the 10 northern counties of the Sierra Nevada to a depth of 400 feet, the actual measured thickness of the auriferous gravels we see today in California. An alternate, second, explanation was championed by the late paleobotanist/geologist Howard Schorn, former Collections Manager of Fossil Plants at the University California Museum of Paleontology. Schorn and others postulated that about 52 million years ago (early Eocene), the marine waters that had covered what's now California's Great Central Valley for several million years began to regress, or retreat. That drop in sea level caused streams flowing westward from the ancestral Sierra Nevada to begin to incise their channels. At around 48 million years ago (early middle Eocene), sea levels began to rise once again when the Domenguine-Ione Seaway re-flooded (transgressed) the proto-Great Central Valley, returning marine conditions to a terrestrial area previously left high and dry. That rise in sea level began to block, or dam, the mouths of the ancient northern Sierra Nevada rivers, among them the Tertiary Yuba River, initially causing gold-rich sediments to accumulate in the moderately downcut inner channels (areas later known to hydraulickers as the fabulous "blue ground"). Continuing incremental sea level increases contributed to the deposition of progressively greater volumes of sedimentary material in the older eroded river courses, completely filling them, until at last the Tertiary Yuba River spread out over the floodplains in wide meandering curves, thus creating by aggradation the bench gravels and chocolate shales--within which the middle Eocene Chalk Bluffs Flora occurs. Yet a third explanation--advocated by a number of geologists---postulates that several highly resistant Paleozoic and Mesozoic metamorphic ridges (so-called "greenstone and greenschist barriers") acted as impedimentary obstacles to most westward draining Eocene rivers, creating natural geographic constriction points behind which waters began to "dam," initiating a vast system of braided streams that eventually began to aggrade. Some 70 species of ancient plants have been identified from the Chalk Bluffs Flora (which refers collectively to the total aggregate of plants obtained from every locality in the middle Eocene auriferous gravels of California's Northern Mother Lode district), including such varieties as: American climbing fern; cinnamon fern; flowering fern (solely from pollen evidence); Mexican cycad; broadleaf lady palm; sarsaparilla vine; crack willow; swamp hickory; an extinct genus of Engelhardia, a tree whose modern types are native to northern India east to Taiwan, Indonesia and the Philippines; Formosan alder; a species of chinquapin now endemic to Vietnam and China; three extinct oaks similar to the living interior live oak, Sierra oak, and Japanese blue oak; Mexican elm; Breadfruit; Pea fig; an extinct fig; Yellow lotus (also called Yellow pond lily); Katsuna tree; a species of Hyperbaena resembling a variety now native to Central America; umbrella magnolia; two species of extinct Cinnamomum (Cinnamon trees); six species of evergreen laurels, including swampbay; Chinese hydrangea; American witch-hazel; American sweetgum (also called Liquidamber, now native to the southeastern United States, Mexico, and Central America); five species of extinct sycamores (one resembles the modern American sycamore), including the magnificent Magnititiea whitneyi (leaves can spread to 13 inches wide; it resembles the living sycamore Platanus lindeniana of east-central Mexico to Guatemala); Cocoplum; Slimleaf rosewood; a species of rosewood that resembles a kind now native to China; a species of Tick clover that is similar to a type now endemic to East Asia; a legume whose closest modern counterpart lives in the Amazon flooplains; Chinese olive; Tree of heaven; Cuban cedar; a spurge (Euphorbia) now endemic to southern Mexico and Central America; East Asian mallotus (also called the "food wrapper plant"); staff vine; a species of Phytocrene now native to Myanmar, Sumatra, Java, and the Philippines; Smooth sumac; an extinct maple that resembles the living Red maple and trident maple (now native to China); mallows (obtained only from pollens); a Cupania tree presently endemic to the South American countries--Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, Brazil, and Bolivia; a species of Thouinidium, a shrub to small tree now common in southern Mexico; a variety of Meliosma, a large brush to small tree, presently native to China; a species of Bridelia, a large shrub or small tree native to southeast Asia; walnut (only from pollens); two species of buckthorne now endemic to southeastern Asia and China; princess vine; Franklin tree; spicewood; black gum (also known as Black tupelo); Tropical almond; Pacific dogwood; Pongame oiltree; American persimmon; black ash; oleander; milkwood; dog-strangling vine; a species of viburnum presently common to Mexico; a species in the genus Mikania, often called hempvine--it's native to Mexico, Central and South America, the West Indies, and the southeastern US; a species that most closely resembles the genus Tylophora, a vine native to tropical and subtropical Asia, Africa, and Australia; a type that most closely matches the genus Premna (mint family), a small tree or shrub common in tropical and subtropical regions of Africa, southern Asia, northern Australia, and several islands in the Pacific and Indian Oceans; a specimen that is quite similar to the extant nettlespurge; forms that most closely match the genus Croton, currently native to Indonesia, Malaysia, Australia, and the western Pacific Ocean islands; a mysterious extinct plant that shows characteristics typical of both Blackjack oak and a sycamore; and the following conifers, all obtained only from palynological specimens blown in from great distances--pine, spruce, and fir. All specimens are middle Eocene in geologic age, roughly 48 to 45 million years old--an awe-inspiring fossil flora whose overall composition resembles a modern subtropical Mexican Elm-Liquidamber forest at the foot of Mount Orizaba in Vera Cruz, Mexico, where rainfall averages 60 to 80 inches a year, and the usual year-round temperature is close to 65 degrees, with no frost. There are also similarities to such modern subtropical forests as those found along the Rio Moctezuma at Tomazunchale, Mexico; to the Liquidamber-Oak and Mexican Elm forests near Coban, Guatemala; and to the Liquidamber forests in the state of Morelos and the eastern Sierra Madre west of Tomazunchale, Mexico. Today, the Chalk Bluffs Flora lies at elevations between 2,500 and and 4,000 feet amid what botanists variously categorize as the Transition Life zone, the Sierra Transition life zone, or the Sierran Lower Montane vegetation zone--an area within California's western Sierra Nevada foothills now dominated by a decidedly Mediterranean-style meteorology; that is to say, summers typified by rather high daytime temperatures (often exceeding 100 degrees), low humidity, and scant rainfall (usually as little as one inch for the entire three month period). Virtually all the effective precipitation occurs during wintertime--when temperatures can drop to 5 degrees Fahrenheit--as frequent heavy rains and occasional snow. It's a land characteristically populated by the following common plants: Azalea (Rhodendron occidentals); Big-leaf maple (Acer macrophyllum); Black cottonwood (Populus trilocarpa); Black oak; (Quercus kelloggii); Canyon live oak (Quercus chrysolepis); Chinquapin (Castanopis sempervirens); Chokecherry (Prunus demissa); Coffeeberry (Rhamnus rubra); Creambush (Holodiscus discolor); Deer brush (Ceanothus integerrimus); Dogwood (Cornus nuttallii); Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga texifolia); Elk clover (Aralia californica); Gooseberry (Ribes roezlii); Hazelnut (Corylus rostrata); Incense cedar (Libocedrus decurrens); Knobcone pine (Pinus attenuata); Labrador tea (Ledum glandulosum); Madrone (Arbutus menzsiesii); Mahala nut (Ceanothus prostratus); Manzanita (Arctostaphylos patula); Mountain mahogany (Cercocarpus betuloides); Mountain misery (Chamaebatia foliosa); Pigeonberry (Rhamnus californica); Poison oak (Rhus Taxicodendron diveriloba); Red alder (Alnus rubra); Serviceberry (Amelanchier alnifolia); Sugar pine (Pinus lambertiana); Sumac (Rhus trilobata); Tan oak (Lithocarpus densiflora); Thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus); Tobacco brush (Ceanothus velutinus); White fir (Abies concolor); Wild grape (Vitis californica); Wild rose (Rosa spp.); Willow (Salix spp.); and Yellow pine (Pinus ponderosa). A major collecting convenience at Chalk Bluff is that the claystone is quite soft. This means that the fossilferous material is easily split with a geology hammer (chisels, optional), or perhaps a brick layer's wide blade tool--as advocated by not a few paleobotanists for all leafiferous localities, even though the tool obviously lacks the necessary punch/mass required to split the more indurated, hardened, leaf-bearing rocks; the upshot: a good old regular geology hammer is best for splitting virtually all leaf-bearing shales. The plants preserved in the chocolate shales have remained most life-like in preservational detail, despite the undeniable fact they've been buried for approximately 48 to 45 million years. For example, several specimens I've uncovered reveal actual original cuticle, a thin wax coating on the upper layer of leaves that helps protect against damage that could interfere with photosynthetic activity. In addition to the paleontologically rewarding leaf-bearing chocolate shales, the Chalk Bluff district also yields locally obvious examples of petrified wood. It's of similar geologic age as the fossil leaves, middle Eocene, but the permineralized wood occurs primarily within auriferous bench gravel beds slightly older than the chocolate shales. Most of the sporadic concentrations of petrified woods lie north of the shale beds just explored for fossil leaves, where it erodes free of the brownish auriferous gravels as hand-sized specimens, mainly. Even though the wood is excellently silicified, replaced by the mineral silicon dioxide, the material is far from gem quality. It has not been agatized or replaced by the kinds of colorful minerals that might justify great lapidary value. Preservation of the woody structure is usually superb, though, so folks with slabbing saws just might want to try sectioning specimens to expose the growth lines. In a historical perspective, petrified wood used to be quite abundant in the coarser auriferous gravel lenses during hydraulic mining days--including occasional spectacular occurrences of standing stone stumps and lengthy fallen logs. The old-time gold seekers removed great quantities of it while they blasted away entire mountainsides with their powerful jets of water, stacking the permineralized organic remains in sizable piles so that they would not interfere with gold extraction activities. Sometimes they used the larger rock logs to line their long flumes, employing with practical ingenuity a plentiful natural resource to help transport water to the operations. Today, petrified wood is only common to locally abundant in the many massive, abandoned surface mines scattered throughout the northern Mother Lode country--notably Buckeye Flat, Sailor Flat, Dutch Flat, North Columbia, Iowa Hill, and Malakoff Diggins--most of it having been carted away decades ago as curiosity pieces. The petrified wood, leaves, seeds, flowering structures, and pollens preserved in the Chalk Bluffs Flora have figured quite prominently in a great geophysical and geomorphological debate: Just how high was the ancestral Sierra Nevada during the geologic past? The traditional view, famously championed by the late paleobotanist Daniel I. Axelrod (and numerous other scientists, of course), is that the Sierra Nevada, as we know it today, is a relatively recent topographic expression, uplifted to its present dramatic elevations mainly during the past five million years--with most of that uplift occurring over the last three million years. Yet, studies based on sophisticated geophysical evaluations of many mountain ranges, combined with paleobotanical leaf character analysis (study of leaf size, shape, venation, and percentage of entire to serrated margins, among other parameters, to help determine the paleoclimate and paleoelevation of a given fossil site), preliminarily suggested quite strongly that the Sierra Nevada, along with the neighboring ancestral Great Basin region, stood just as high if not higher during middle Eocene Chalk Bluff times than at present. Finally, though, after analyzing multitudinous information amassed from disparate disciplines of scientific research, investigators seem to be gradually approaching a consensus--namely, that the ancestral central to southern Sierra Nevada existed during Eocene times as a relatively low-lying, gradual-gradient western slope to a high plateau region, the so-called Nevadaplano, that stretched eastward across present-day Nevada, an Eocene upland area that rose as high, if not higher, than the peak elevations seen there today. At around 16 million years ago, the Nevadaplano began to collapse, drop, through extensional geophysical strains associated with incipient formation of the Great Basin, eventually falling to roughly present-day elevations by about 6.8 million years ago. Which would mean, ultimately, that the central to southern Sierra has indeed been dramatically uplifted during the past five million years or so. On the other hand, today's northern Sierran areas would have remained at around the same elevations as those that existed during deposition of the Eocene auriferous gravels some 48 to 38 million years ago. If that indeed turns out to be the case, everyone involved in the Sierran elevation studies can claim a partial victory: the grand solution to the Sierra Nevada Eocene elevation problem would involve a major compromise--around two-thirds of the Sierran length would have been greatly uplifted during the past five million years. Today, at an elevation of roughly 3,000 feet, the Chalk Bluff fossil field is theoretically accessible to year-round exploration. Realistically, though, you'll probably wish to consider skipping a wintertime visit, due to the usual heavy rains and occasional snowstorms that effectively prohibit efficient and comfortable explorations. Also, if one calculates that one could possibly beat the invariable extreme summertime heat in California's Great Central Valley by fleeing to Chalk Bluff--forget it. The altitude there is just not sufficient to influence an appreciable daytime temperature reduction from "down below." Too, during summer, due to meteorological inversion layers, even the evenings and nights often range appreciably warmer than what's experienced in the central valley flatlands. All in all, late spring (after the rainy season) and early to mid fall (before seasonal precipitation patterns) usually offer the most reliably comfortable conditions for hiking, for efficient paleobotanical investigations. Remember of course that all fossil sites are off-limits without permission from the landowners. Access to the Chalk Bluff district is via a system of excellent asphalted surface streets and well-graded dirt roads. Most conventional vehicles in reliable operating condition should have no trouble reaching the fossiliferous area. The main dirt road in can turn treacherous during the rainy season, of course, especially if humungous logging rigs have rumbled through, transforming the route into a hazardous quagmire. Too, throughout the Sierra freezing season, be extra alert for "black ice" along the roads--patchy frozen invisible films that can send unsuspecting drivers into a panicked slide. Today, the Chalk Bluff fossil locality lies amidst what botanists often call the Sierran Lower Montane vegetation zone, characterized by ponderosa pine, sugar pine, knobcone pine, willow, Black cottonwood, alder, manzanita, and madrone. Yet, during middle Eocene times some 48 to 45 million years ago, this very area would have held a stagnant oxbow lake within the vast floodplains of a meandering Amazon-like river, where countless leaves, seeds, flowering structures, and pollens from a subtropical forest fell into the gradually accumulating clays of oxygen-poor waters, preserving such plant life as palm, magnolia, swampbay, sarsaparilla vine, breadfruit, tupelo, fig, persimmon, cinnamon, sycamore, and liquidamber in amazing detail. |

|

|

|

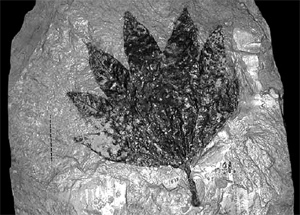

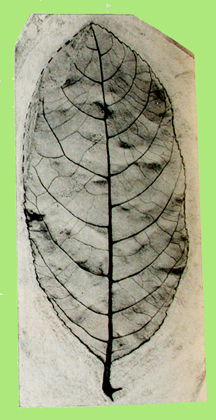

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: A leaf from the extinct sycamore Macginitiea whitneyi, collected between 1933 and 1938 by paleobotanist H. D. Macginitie (who originally called the specimen Platanophyllum whitneyi) from the Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine, middle Eocene auriferous gravels, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada. It resembles the living sycamore Platanus lindeniana of east-central Mexico to Guatemala. Photograph courtesy paleobotanist Diane M. Erwin. Right--A leaf from the extinct sycamore, now known as Macginitiea whitneyi, collected in the late 1860s by Charles D. Voy--acclaimed naturalist and indefatigable gatherer of South Sea Islands ethnological items--from the Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine, middle Eocene auriferous gravels, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada. In 1878, Lesquereux named this Aralia whitneyi in honor of a former California State Geologist. Image courtesy Lorraine Cazassa. Please Note: All fossil sites are off-limits without permission from the landowners. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Two leaves from the middle Eocene auriferous gravels, Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada. Left to right: Matches closely what paleobotanist H. D. Macguinitie called Quercus distincta, an extinct species of evergreen Eocene oak similar to the living Coast live oak. Right--A specimen that matches what H. D. Macginitie called Phytocrene sordida, a species that most closely resembles a living Phytocrene evergreen vine now native to Myanmar, Sumatra, Java, and the Philippines; that distinctive reddish coloration to the Chalk Bluffs Flora specimen signifies that its original cuticle has been preserved intact--a genuine rarity in the fossil record. The cuticle is that thin layer on the upper epidermis of leaves that helps protect against mechanical injury, excessive water loss, and fungal attack. Photos courtesy the California Academy of Sciences from a publicly accessible site. Please Note: All fossil sites are off-limits without permission from the landowners. |

|

|

|

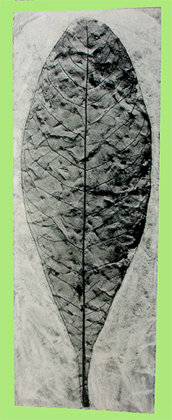

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: A leaf from a specimen that appears to represent what H. D. MacGinitie called Mallotus riparios in his classic monograph on the Chalk Bluffs Flora, A Middle Eocene Flora From The Central Sierra Nevada, Carnegie Institute of Washington Publication 534, 1941. Mallotus riparios is most closely related to the living M. japonicus and M. tenuifolius, species now native to warm-temperate Japan and China--from Chekiang to western Hupeh and Szechwan. Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine. Right--A leaf from the middle Eocene auriferous gravels, Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada. Seems quite close in appearance to what paleobotanist H. D. Macguinitie called Persea pseudo-carolinensis, which is similar to the modern swampbay, an evergreen tree native to the southeastern United States. Please Note: All fossil sites are off-limits without permission from the landowners. |

|

|

|

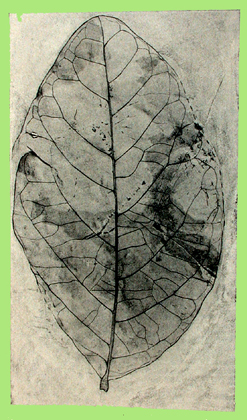

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left: Leaves that resemble what H. D. MacGinitie called Inga ionensis in his classic monograph on the Chalk Bluffs Flora, A Middle Eocene Flora From The Central Sierra Nevada, Carnegie Institute of Washington Publication 534, 1941. Living members of the genus Inga (a member of the legume family) are indigenou to subtropical areas of Mexico, Central America, and South America. Middle Eocene auriferous gravels, Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine. Right--A leaf from the middle Eocene auriferous gravels, Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada. Seems quite close in appearance to what paleobotanist H. D. Macguinitie called Persea pseudo-carolinensis, which is similar to the modern swampbay, an evergreen tree native to the southeastern United States. The specimen consists of relatively unaltered cuticle material remaining from the original leaf; unfortunately, portions of the cuticle (near the top of the leaf) had already weathered away before it was collected. A faint imprint of the eroded cuticle can be seen at top of specimen. Please Note: All fossil sites are off-limits without permission from the landowners. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: A leaf from the middle Eocene auriferous gravels, Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada. Quite similar to what paleobotanist H. D. Macguinitie called Acer aequidentatum, an extinct maple that shows characteristis of two living species--the Red maple and the trident maple (now native to China). Photo courtesy the California Academy of Sciences from a publicly accessible site. Right--A freshly dug leaf from the middle Eocene auriferous gravels, Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada. It's one of several types of evergreen laurels that paleobotanist H. D. MacGinitie described from the Chalk Bluffs Flora in his classic work A Middle Eocene Flora From The Central Sierra Nevada, 1941, Carnegie Institute of Washington Publication 534. Please Note: All fossil sites are off-limits without permission from the landowners. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left and right: Leaves from the middle Eocene auriferous gravels, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada. Left--A leaf from the extinct sycamore Macginitiea whitneyi, Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine It resembles the living sycamore Platanus lindeniana of east-central Mexico to Guatemala. Scale at lower left is in inches (top, beginning with blue bar at far left) and centimeters. Photograph courtesy the California Academy of Sciences (from a publicly accessible site). I edited and processed the image through photoshop. Right--Two overlapping leaves from the Malakoff Diggins hydraulic gold mine. Collected by the late paleobotanists Howard Schorn and Jack A. Wolfe on August 14, 2003. Larger of the two leaves is closest to what paleobotanist H. D. MacGinitie called Hydrangeo californica--an extinct hydrangea (hortensia) that resembles the living Hydrangeo strigosa, native to China. Smaller specimen at lower right agrees closely with what paleobotanist H. D. MacGinitie called Laurophyllum fremontensis, an extinct member of the evergreen laurel family that has no direct modern counterpart, though it does show close resemblances to three living genera: Cryptocarya--native to Andaman Is., Argentina Northeast, Assam, Bangladesh, Bismarck Archipelago, Borneo, Brazil North, Brazil Northeast, Brazil South, Brazil Southeast, Brazil West-Central, Cambodia, Cape Provinces, Chile Central, Chile South, China South-Central, China Southeast, Christmas I., Comoros, East Himalaya, Ecuador, Fiji, French Guiana, Hainan, Hawaii, India, Jawa, KwaZulu-Natal, Laos, Lesser Sunda Is., Madagascar, Malawi, Malaya, Maluku, Mozambique, Myanmar, Nansei-shoto, Nepal, New Caledonia, New Guinea, New South Wales, Nicobar Is., Niue, Norfolk Is., Northern Provinces, Northern Territory, Panamá, Peru, Philippines, Queensland, Samoa, Solomon Is., Sri Lanka, Sulawesi, Sumatera, Swaziland, Taiwan, Tanzania, Thailand, Tibet, Tonga, Uruguay, Vanuatu, Vietnam, Western Australia, Zambia, Zimbabwe; Machilus--endemic to Bangladesh, Cambodia, China South-Central, China Southeast, Hainan, India, Japan, Jawa, Kazan-retto, Korea, Laos, Lesser Sunda Is., Myanmar, Ogasawara-shoto, Sumatera, Taiwan, Vietnam; and Nectandra--now lives in Argentina Northeast, Argentina Northwest, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil North, Brazil Northeast, Brazil South, Brazil Southeast, Brazil West-Central, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, French Guiana, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Leeward Is., Mexico Central, Mexico Gulf, Mexico Northeast, Mexico Northwest, Mexico Southeast, Mexico Southwest, Nicaragua, Panamá, Paraguay, Peru, Puerto Rico, Suriname, Trinidad-Tobago, Uruguay, Venezuela, Windward Is. Please Note: All fossil sites are off-limits without permission from the landowners. At Malakoff Diggnins, one must first secure a permit from the California State Park officials prior to a collecting expedition--a permit granted solely to individuals with a minimum B.S. degree from an accredited university who seek to undertake scientific research projects that can be fully authenticated by the petitioned authorities. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. A fossil magnolia leaf from the middle Eocene auriferous gravels, Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada, figured by paleobotanist H. D. MacGinitie in his classic work A Middle Eocene Flora From The Central Sierra Nevada, Carnegie Institute of Washington Publication 534, 1941. Called scientifically Magnolia dayana--an extinct magnolia that closely resembles the living umbrella magnolia, native to the Appalachian Mountains, the Ozarks, and the Ouachita Mountains of the eastern United States. Right--A leaf from the middle Eocene auriferous gravels, Chalk Bluff hyraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada, figured by paleobotanist H. D. MacGinitie in his classic work A Middle Eocene Flora From The Central Sierra Nevada, Carnegie Institute of Washington Publication 534, 1941. Called scientifically Pongamia ovata, which is the Eocene equivalent of the living Pongame oiltree Millettia pinnata (formerly called Pongamia pinnata--whose seed oil is extracted for biodiesel fuel), a member of the the pea family native to parts of the Indian subcontinent, China, Japan, Malaysia, Australia, and Pacific islands. Please Note: All fossil sites are off-limits without permission from the landowners. |

|

|

|

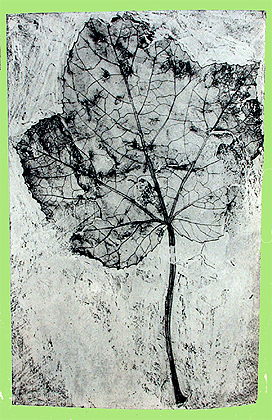

Click on the images for larger pictures. Fossil leaves from the middle Eocene auriferous gravels, Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada, figured by paleobotanist H. D. MacGinitie in his classic work A Middle Eocene Flora From The Central Sierra Nevada, 1941, Carnegie Institute of Washington Publication 534. Left--Platanus appendiculata, an extinct sycamore that is similar to the modern American sycamore, native to the eastern to central United States and northeastern Mexico. Right--Liquidamber californicum, an extinct liquidamber which resembles the living American sweetgum, native the southeastern United States, Mexico, and Central America. Please Note: All fossil sites are off-limits without permission from the landowners. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictueres. Fossil leaves from the middle Eocene auriferous gravels, Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada, figured by paleobotanist H. D. MacGinitie in his classic work A Middle Eocene Flora From The Central Sierra Nevada, 1941, Carnegie Institute of Washington Publication 534. Left--Neolitsea lata, an extinct member of the laurel family, with evergreen leaves, that resemblances the modern Neolitsea chuii of southern China, a tree that grows to 60 feet. Right--Rhamnus calyptus, a presumed extinct buckthorn that is quite similar to the living Rhamnus nepalensis native to India, China, and Malaysia. Please Note: All fossil sites are off-limits without permission from the landowners. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Two leaves from the middle Eocene auriferous gravels, Buckeye Flat hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada. Left to right: A specimen that in secondary venation, margins, and overall shape closely resembles what paleobotanist H. D. MacGinitie identified as Chaetoptelea pseudo-fulva, an extinct species that is similar to the living Mexican elm, endemic to Mexico and Central America. Right--One of several species of evergreen laurels that H. D. MacGinitie described from the middle Eocene Chalk Bluffs Flora. A significant specimen. It's the first fossil leaf that provides unequivocal paleobotanical evidence that the middle Eocene auriferous gravels can be correlated stratigraphically with the leaf-bearing middle Eocene Ione Formation in the vicinity Ione, Amador County, California, roughly 62 miles southwest of the Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine. The leaf came from an horizon in the middle Eocene auriferous gravels that bears specimens that are not only identical to the leaves recovered from the Ione Formation (entire margins, with no serrations or lobes, for example), but are also preserved with the same distinctive reddish-brown iron-stained coloration; this is in obvious contrast to the fossil flora found in the auriferous gravels' chocolate shales, which produce numerous leaves with serrations and lobes--all invariably preserved as dark brown to black carbonized impressions (Chalk Bluffs Flora leaves with original cuticle are of course preserved in orange to reddish tones). The implications of this discovery are far-reaching, indeed. For example, the middle Eocene Ione Flora (obtained from the Ione Formation, in the general area of Ione, California, lower western foothills of the Sierra Nevada) accumulated in close proximity to sea level along the eastern shores of the Domengine-Ione Seaway, which had transgressed (flooded) the Tertiary Great Central Valley, while simultaneously the Buckeye Flat middle Eocene plants lived at an altitude between 3,000 and 4,000 feet; thus, the sea level Ione leaves--all with entire (smooth) margins--can no longer be used as reliable indicators of a baseline sea level paleoenvironment, since identical botanical forms also occur in the higher-elevation Chalk Bluffs Flora of Buckeye Flat, where lobed and serrated fossil leaves indicate relatively cooler paleo-temperatures. Paleobotanist H. D. MacGinitie actually began his monumental investigations of the Chalk Bluffs Flora at Buckeye Flat in 1933 before he re-discovered the stratigraphically correlative chocolate shale beds at the Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine. Please Note: All fossil sites are off-limits without permission from the landowners. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: A chunk of as-yet unidentified petrified wood from the middle Eocene auriferous gravels, Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada. Petrified wood used to be abundant at the Chalk Bluff mine (and most of the other numerous 19th Century hydraulic operations in California's northern Mother Lode district), including fallen logs and quite sizable pieces that the old time hydraulickers stacked in great piles so that the Eocene permineralized botanic specimens would not interfere with gold extraction activities. Right--An archival photograph of folks sitting atop a petrified log from the middle Eocene auriferous gravels, exposed by hydraulickers in the mid 1800s at the Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada. Photograph taken sometime between 1933 and 1938. From the volume A Middle Eocene Flora From The Central Sierra Nevada, by H. D. MacGinitie, Carnegie Institute of Washington Publication 534, 1941. Please Note: All fossil sites are off-limits without permission from the landowners. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: Petrified wood (genus-species undetermined) weathers out of the middle Eocene auriferous gravels at the Buckeye Flat hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada; for scale perspective, that geology hammer is 13 inches long. Paleobotanist H. D. MacGinitie actually began his monumental investigations of the Chalk Bluffs Flora at Buckeye Flat in 1933 before he re-discovered the stratigraphically correlative chocolate shale beds at the Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine. Right--A petrified burl (genus-species undetermined) weathers out of the middle Eocene auriferous gravels at the Buckeye Flat hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada; for scale perspective, that geology hammer is 13 inches long. Paleobotanist H. D. MacGinitie actually began his monumental investigations of the Chalk Bluffs Flora at Buckeye Flat in 1933 before he re-discovered the stratigraphically correlative chocolate shale beds at the Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine. Please Note: All fossil sites are off-limits without permission from the landowners. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right--Petrified wood (genus-species undetermined) weathers out of the middle Eocene auriferous gravels at the Buckeye Flat hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada; for scale perspective, that geology hammer is 13 inches long. Right--An archival photograph from the classic volume A Middle Eocene Flora From The Central Sierra Nevada, by H. D. MacGinitie, Carnegie Institute of Washington Publication 534, 1941. That's a stump from an extinct sycamore embedded in place in the middle Eocene auriferous gravels at the Buckeye Flat hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada; photograph taken between 1933 and 1938. Paleobotanist H. D. MacGinitie actually began his monumental investigations of the Chalk Bluffs Flora at Buckeye Flat in the early 1930s before he re-discovered the stratigraphically correlative chocolate shale beds at the Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine. Please Note: All fossil sites are off-limits without permission from the landowners. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. A number of homes in Nevada County, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada--the heart of historic hydraulic gold mining territory during the mid to late 1800s--have fireplaces constructed of petrified wood collected from local exposures of middle Eocene auriferous gravels left behind at the neighboring hydraulic pits. Left to right--Two views of a fireplace at a private residence in Dutch Flat, Nevada County, California--a structure "hewn" from petrified wood gathered from the nearby middle Eocene auriferous gravels. Photographs courtesy anonymous individuals at specific web sites. Please Note: All fossil sites in the auriferous gravels are off-limits without permission from the landowners. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. A number of homes in Nevada County, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada--the heart of historic hydraulic gold mining territory during the mid to late 1800s--have fireplaces constructed of petrified wood collected from local exposures of middle Eocene auriferous gravels left behind at the neighboring hydraulic pits. Left to right--fireplaces at private residences in Grass Valley and Nevada City, respectively, Nevada County, California--structures "hewn" from petrified wood gathered from the nearby middle Eocene auriferous gravels. Photographs courtesy anonymous individuals at specific web sites. Please Note: All fossil sites in the auriferous gravels are off-limits without permission from the landowners. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. A number of homes in Nevada County, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada--the heart of historic hydraulic gold mining territory during the mid to late 1800s--have fireplaces constructed of petrified wood collected from local exposures of middle Eocene auriferous gravels left behind at the neighboring hydraulic pits. Left to right--fireplaces at private residences in Grass Valley and Nevada City, respectively, Nevada County, California--structures "hewn" from petrified wood gathered from the nearby middle Eocene auriferous gravels. Photographs courtesy anonymous individuals at specific web sites. Please Note: All fossil sites in the auriferous gravels are off-limits without permission from the landowners. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: A panoramic perspective, looking roughly northeast, across the great Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada. Hydraulickers worked everything here from the immediate foreground to the reddish-brown cliff at upper left to center, ultimately excavating downward approximately 400 feet through the auriferous gravels to the local metamorphic bedrock, where the fabulous "inner channel" (or "blue ground")--only tens of feet wide in most places--yielded vast fortunes in gold. The younger bench gravels, within which the leaf-bearing chocolate shales occur, yielded far inferior concentrations of the precious metal. Chalk Bluff ridge, proper, lies along the skyline; it's composed of latest Eocene (about 34 million years old) rhyolite tuff. Right--A panoramic perspective, looking roughly northeast, across the great Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada. Hydraulickers worked everything here from the immediate foreground to the reddish-brown cliff at upper left to center, ultimately excavating downward approximately 400 feet through the auriferous gravels to the local metamorphic bedrock, where the fabulous "inner channel" (or "blue ground")--only tens of feet wide in most places--yielded vast fortunes in gold. The younger bench gravels, within which the leaf-bearing chocolate shales occur, yielded far inferior concentrations of the precious metal. Chalk Bluff ridge, proper, lies along the skyline; it's composed of latest Eocene (about 34 million years old) rhyolite tuff. Photograph courtesy the late paleobotanist Howard Schorn. Please Note: All fossil sites are off-limits without permission from the landowners. |

|

|

|

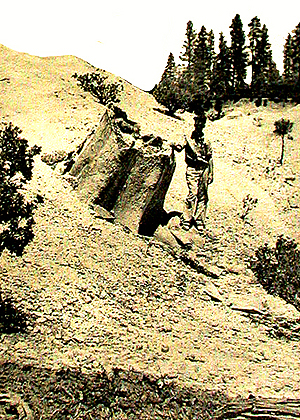

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: Along the main path through the Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada. Chalk Bluff ridge, proper, lies directly ahead; it's composed of latest Eocene-age (approximately 34 million years old) unfossiliferous rhyolite tuff. Right--Looking southward from the rim of the great Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada. Those 200 to 300 foot cliffs of middle Eocene auriferous gravels were created when mid 19th Century hydraulickers burrowed down to local metamorphic bedrock (at least 400 feet below the original surface of the land), in search of high grade gold concentrations. Please Note: All fossil sites are off-limits without permission from the landowners. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left and right: Two views looking northeast to roughly the same southern Chalk Bluff ridge section, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada. Youngest acummulations of the middle Eocene aurifeous gravels comprise the slopes. Fossil leaves occur in lenticular clay lenses about halfway up the incline. Photo at left snapped in latest 20th Century. Right--photograph taken between 1933 and 1938; from the volume A Middle Eocene Flora From The Central Sierra Nevada, by H. D. MacGinitie, Carnegie Institute of Washington Publication 534, 1941. Please Note: All fossil sites are off-limits without permission from the landowners. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: Left--An unexploited cliff face of middle Eocene auriferous gravels that the mid 19th Century hydraulickers left behind at the Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine, California. Note the progressive upward fining of the gold-bearing sedimentary material, culminating in a localized exposure of the leaf-bearing chocolate shales at the very top. Right--A "sneaky"-quasi-hidden exposure of leaf-bearing chocolate shales (marked with the green letters Chocolate Shales), interbedded with the middle Eocene auriferous gravels, Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada. For scale perspective, that geology hammer, just to the right of the green lettering, is 13 inches long. Please Note: All fossil sites are off-limits without permission from the landowners. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--An encounter with an unexcavated bed of leaf-bearing chocolate shales (marked with the black letters at middle left--CS), interbedded with the middle Eocene auriferous gravels, Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada. Right--A closeup of the middle Eocene auriferous gravels at the Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada; white quartz pebbles and darker-colored metamorphic clasts set in a matrix of coarse sand comprise the gold-bearing gravels. That geology hammer is 13 inches long, by the way. Note clumps of Sierra lupine (Lupinus grayi) at base of the exposure; photograph taken in May. Please Note: All fossil sites are off-limits without permission from the landowners. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--Freshly excavated leaf-bearing chocolate shales at the great Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada. Some 70 species of fossil plants--mostly similar to subtropical types that now grow in southern Mexico--have been described from the middle Eocene Chalk Bluffs Flora--that is, the total aggregate of specimens recovered from all localities in the chocolate shales exposed by hydraulic methods in the northern Sierra Nevada district during the mid to late 1800s. That geology hammer is 13 inches long, by the way. Right--Clumps of Sierra lupine (Lupinus grayi) observed at the great Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada; photograph taken in May. Please Note: All fossil sites are off-limits without permission from the landowners. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--Scotch Broom (Cytisus scoparius), a member of the Pea family, blooming at the great Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada. A plant native to southern Europe and northern Africa; photograph taken in May. Right--An undisturbed exposure of leaf-yielding chocolate shales (marked by the black letters--CS, at lower right) lies within the middle Eocene auriferous gravels at the Buckeye Flat hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada. Paleobotanist H. D. MacGinitie began his monumental scientific analysis of the Chalk Bluffs Flora here at Buckeye Flat in 1933, before he rediscovered the stratigraphically correlative and prolific chocolate shale beds at the Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine. Please Note: All fossil sites are off-limits without permission from the landowners. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--The late paleobotanist Howard Schorn (from 1964 to 1993, Collections Manager of Fossil Plants at the University California Museum of Paleontology) collects fossil leaves at the Buckeye Flat hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada, from a major quarrying excavation in chocolate shales that accumulated during middle Eocene times (about 48 to 45 million years ago) in a subtropical climate similar to today's southern Mexico along the vast floodplains of the Tertiary Yuba River, which dropped great quantities of gold. Photograph taken August 13, 2003. Paleobotanist H. D. MacGinitie began his monumental scientific analysis of the Chalk Bluffs Flora here at Buckeye Flat in 1933, before he rediscovered the stratigraphically correlative and prolific chocolate shale beds at the Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine. Right--The late paleobotanist Jack A. Wolfe (longtime member of the United States Geological Survey) collects fossil leaves at the Buckeye Flat hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada, from chocolate shales that accumulated during middle Eocene times (about 48 to 45 million years ago) in a subtropical climate similar to today's southern Mexico along the vast floodplains of the Tertiary Yuba River, which dropped great quantities of gold. Photograph taken August 13, 2003. Paleobotanist H. D. MacGinitie began his monumental scientific analysis of the Chalk Bluffs Flora here at Buckeye Flat in 1933, before he rediscovered the stratigraphically correlative and prolific chocolate shale beds at the Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine. Please Note: All fossil sites are off-limits without permission from the landowners. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--The late paleobotanist Howard Schorn (from 1964 to 1993, Collections Manager of Fossil Plants at the University California Museum of Paleontology) assumes a classic paleobotanical position to collect fossil leaves at the Buckeye Flat hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada, from a major quarrying excavation in chocolate shales that accumulated during middle Eocene times (about 48 to 45 million years ago) in a subtropical climate similar to today's southern Mexico along the vast floodplains of the Tertiary Yuba River, which dropped great quantities of gold. Photograph taken August 13, 2003. Paleobotanist H. D. MacGinitie began his monumental scientific analysis of the Chalk Bluffs Flora here at Buckeye Flat in 1933, before he rediscovered the stratigraphically correlative and prolific chocolate shale beds at the Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine. Right--The late paleobotanist Jack A. Wolfe (longtime member of the United States Geological Survey) collects fossil leaves at the Malakoff Diggins hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada. Photograph taken August 14, 2003. Please Note: All fossil sites are off-limits without permission from the landowners. At Malakoff Diggnins, one must first secure a permit from the California State Park officials prior to a collecting expedition--a permit granted solely to individuals with a minimum B.S. degree from an accredited university who seek to undertake scientific research projects that can be fully authenticated by the petitioned authorities. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--A major quarrying excavation in chocolate shales at the Buckeye Flat hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada; the leaf-bearing shales accumulated during middle Eocene times (about 48 to 45 million years ago) in a subtropical climate similar to today's southern Mexico along the vast floodplains of the Tertiary Yuba River, which dropped great quantities of gold. Paleobotanist H. D. MacGinitie began his monumental scientific analysis of the Chalk Bluffs Flora here at Buckeye Flat in 1933, before he rediscovered the stratigraphically correlative and prolific chocolate shale beds at the Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine. Right--Cliffs of middle Eocene auriferous gravels left behind by mid 19th Century hydraulickers at the Malakoff Diggins hydraulic gold mine, western slopes of California's Sierra Nevada---but one of numerous such abandoned open pit gold-extraction localities in Northern California that operated from roughly 1855 to 1884. Please Note: All fossil sites are off-limits without permission from the landowners. At Malakoff Diggnins, one must first secure a permit from the California State Park officials prior to a collecting expedition--a permit granted solely to individuals with a minimum B.S. degree from an accredited university who seek to undertake scientific research projects that can be fully authenticated by the petitioned authorities. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left and right--Middle Eocene auriferous gravels remain untouched at the Malakoff Diggins hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada--but one of numerous such abandoned open pit gold-extraction localities in Northern California that operated from roughly 1855 to 1884. Please Note: All fossil sites are off-limits without permission from the landowners. At Malakoff Diggnins, one must first secure a permit from the California State Park officials prior to a collecting expedition--a permit granted solely to individuals with a minimum B.S. degree from an accredited university who seek to undertake scientific research projects that can be fully authenticated by the petitioned authorities. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--A pond develops at the base of a cliff of middle Eocene auriferous gravels left behind at the Dutch Flat hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada--but one of many abandoned open pit gold-extraction sites in Northern California that operated from roughly 1855 to 1884. Photograph courtesy Wayne Hsieh. Right--One of the most accessible, extensive exposures of unexploited middle Eocene auriferous gravels lies in this cut along the northern side of Interstate 80, about 1 mile east of the Gold Run Rest Stop. The roadcut runs for approximately a half mile, revealing in wonderful geologic detail the fossil thalwegs of the Tertiary Yuba River, which dropped great quantities of gold here. A Google Earth street car perspective that I edited and processed through photoshop. Please Note: All fossil sites are off-limits without permission from the landowners. |

|

|

|

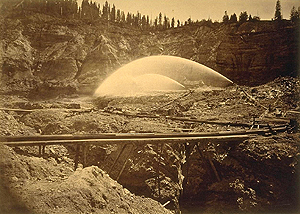

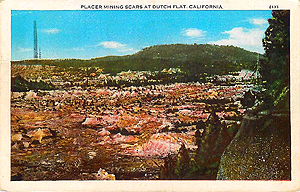

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--A vintage 1879 photograph taken by Carleton E. Watkins at the active Boston hydraulic gold mine, Nevada County, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada; I edited and processed the image through photoshop. The powerful hydraulic monitors dislodged the gold by washing away entire hills and mountainsides composed of middle Eocene auriferous gravels, deposited some 48 to 38 million years ago by the Tertiary Yuba River. Incidental to the gold extraction activities, in addition to encountering locally abundant examples of petrified wood, the old time hydaulickers also often exposed world-class accumulations of fossil leaves preserved in chocolate-colored shales interbedded with the coarse gold-bearing gravels and sands. Right--A vintage 1933 postcard that depicts that aftermath of 19th century hydraulic mining at the Dutch Flat hydraulic gold mine, Nevada County, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada; I edited and processed the image through photoshop. The middle Eocene auriferous gravels here produced unfathomable fortunes in gold during the mid to late 1800s. Please Note: All fossil sites are off-limits without permission from the landowners. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--The late paleobotanists Howard Schorn (at left--April 26, 1933-October 17, 2013) and Jack A. Wolfe (July 10, 1936-August 12, 2005) by a rented U-Haul van at the Northern Queen Inn, Nevada City, California, on August 18, 2003. Truck is filled with boxes of middle Eocene fossil leaves that Schorn, Wolfe, and geologist/geophysicist Clement G. Chase collected from many abandoned hydraulic gold mines, northern Sierra Nevada district, California. Howard Schorn is preparing here to transport that important collection back to the archival paleobotanical repository at the University California Museum of Paleontology in Berkeley. Right--Paleobotanist Howard Schorn delivers a fossil-filled U-Haul truck to the University California Museum of Paleontology, on campus at the University of California, Berkeley. The vehicle contains boxes of middle Eocene fossil leaves that Schorn, paleobotanist Jack A. Wolfe, and geologist/geophysicist Clement G. Chase collected from many abandoned hydraulic gold mines, northern Sierra Nevada, California, during a paleobotanical expedition in the summer of 2003. Photograph taken on August 18, 2003. Please Note: All fossil sites are off-limits without permission from the landowners. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left and right: Paleobotanist Howard Schorn completes the transfer of boxes of middle Eocene leaves to the archival paleobotanical collections at the University California Museum of Paleontology in Berkeley. Howard Schorn, paleobotanist Jack A. Wolfe, and geologist/geophysicist Clement G. Chase collected the fossils from many abandoned hydraulic gold mines, northern Sierra Nevada, California, during a paleobotanical expedition in the summer of 2003. Photograph taken on August 18, 2003. Please Note: All fossil sites are off-limits without permission from the landowners. |

|

|

|

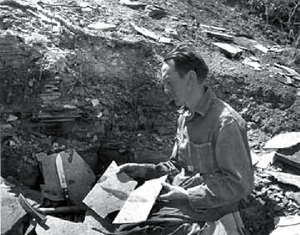

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--Paleobotanist Harry D. MacGinitie (left, with cane), with paleobotanist Jack A. Wolfe, at University California Berkeley, 1980. Photograph courtesy the University California Museum of Paleontology. Right--Paleobotanist Harry D. MacGinitie excavating the classic late Eocene paper shales at Florissant, Colorado--around 1936–37--for fossil leaves (and insects). Photograph courtesy Herbert W. Meyer. H.D. MacGinitie wrote the definitive paleobotanical monograph on the Chalk Bluffs Flora, entitled A Middle Eocene Flora From The Central Sierra Nevada, 1941, Carnegie Institute of Washington Publication 534. Please Note: All fossil sites are off-limits without permission from the landowners. |

|