|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Between the years 1848 and 1932, an estimated $1 billion worth of gold was taken from California at the old historical price of 18 to 20 dollars per troy ounce. Most of the early gold came from the incredibly rich and justifiably famous placer deposits in the foothills of the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada. During the first five years of California's Gold Rush, for example--1848 to 1853--the 49ers removed some 12 million ounces of the precious "yellow stuff." Another significant percentage of the total is credited to intensive dredging operations conducted on several major stream courses in Northern California, particularly along the American and Yuba Rivers; from the 1890s to 1932, the dredgers likely accounted for at least 10 million ounces of gold. In addition to the placer/dredge mines, rich lode ore deposits in the vicinity of Coloma, Nevada City/Grass Valley (they are contiguous communities), Jackson, San Andreas, Angels Camp, Columbia, Sonoroa, and Mariposa also produced millions upon millions in gold. But perhaps the least-appreciated means of recovering the abundant gold of the Gold Rush era was by hydraulic mining. Hydraulicking began only a few years after the gold discovery at Coloma, California, on January 24, 1848, when prospectors, searching farther east up the stream courses, found gold in gravel deposits unrelated geologically to the placer accumulations farther down stream. This gold was locked away in the auriferous or gold-bearing gravel, a stratigraphic interval consisting of interbedded c1ay, silt, sand, pebbles, cobbles, and boulders whose origin was obviously related to long-vanished river channels many millions of years old. In the mid to late 1800s, most geologists and paleobotanists initially believed that all auriferous gravels deposited by the ancestral Tertiary Yuba River and its related Cenozoic tributaries were Miocene in geologic age, roughly 23 to 10 million years old, but later geologic analyses established them entirely of Eocene age, probably 48 to 38 million years old. To get at the coveted metal, the miners employed hydraulic mining--that is, they directed high-pressured jets of water at the auriferous gravel to wash out the gold-rich concentrations hidden within the gravel beds. In the process, they often blasted away entire mountainsides to force massive volumes of potentially gold-rich sludge through a system of sluices, eventually capturing the locally prolific flakes and nuggets of aurum. A conservative estimate suggests that hydraulickers washed away more material than the total removed during excavations of the Panama Canal. Nobody knows for certain just how much gold the hydraulic method recovered--no reliable records were ever kept--but the general consensus among mining historians is that from 1855 to 1884, somewhat under a quarter of the $1 billion in gold can be accounted for by hydraulic mining (approximately 11 million ounces of gold), calculated of course at the antiquated price of about 20 dollars per troy ounce. In 1884, the legally binding landmark Sawyer Decision effectively abolished all major California hydraulicking operations: United States Circuit Judge Lorenzo B. Sawyer issued an injunction which prohibited uncontrolled disposal of hydraulic debris into the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers. This alone probably would not have been enough to stop the practice, but the Sawyer ruling additionally stated that the tributaries of those rivers must also remain free of hydraulic tailings. Today, probably the most accessible place to view a thick sequence of undisturbed auriferous gravel lies in the roadcut on the north side of Interstate 80 just east of the rest stop at Gold Run, between Auburn and Reno. Locally extensive deposits of auriferous gravels can also be investigated at many of the long-abandoned hydraulic mines--specifically at such sites as Howland Flat, St. Louis, Port Wine, Chalk Bluff, ScaIes, Malakoff Diggins, North San Juan, Iowa City, Cherokee, Quaker Flat, Dutch Flat, Buckeye Flat, Sailor Flat, and La Porte. In addition to exposing extensive deposits of auriferous gravel at La Porte, northern Sierra Nevada territory, the hydraulic miners also brought to light a remarkable and paleontologically significant fossiliferous horizon associated with the gold-bearing rocks: a regionally limited exposure of reworked and re-deposited rhyodacite volcanic tuff which yields some 43 species of ancient plants, mainly beautiful carbonized leaves, dated radiometrically (through radioactive isotope analyses) at around 34.2 million years old. The fossils are thus latest Eocene in geologic age, younger by several million years than the gold-bearing gravels upon which they discomformably rest. Appropriately enough, geologists have named this leaf-bearing deposit of hardened volcanic ash the La Porte Tuff, and the plants that occur in it faithfully record a key interval of botanic life on our planet. La Porte lies in the extreme southern sector of P1umas County, California. But before a visit to the fossil 1oca1ity, consider conducting some preliminary adventures: sightseeing in La Porte, a truly scenic mountain community situated amidst the rich mixed conifer forest of the northern Sierra Nevada. La Porte rests an an elevation of approximately 5,000 feet (when the furnace-fire heat of summer begins to flare in the Great Central Valley to the west, this area certainly provides a most refreshing and cooling refuge)--probably close to the same altitude that existed during deposition of the La Porte Tuff 34.2 million years ago; that's because, in a geomorphological sense, the northern Sierra Nevada has remained at approximately today's height since at least 50 million years ago while, conversely, the central to southern Sierra Nevada has been greatly uplifted since about five million years ago. The history of La Porte begins in 1850 when prospectors discovered placer gold on Rabbit Creek at the head of Little Grass Va1ley. Early arrivals christened the site Rabbit Diggings, a name which stuck for several years. Major hydraulicking did not begin in the region until 1855, but by then the town was already bustling with its own hotel, stores, post office, and saloons. Hydraulic mining kept the community in "bacon and beans" for the next 16 years, as the auriferous gravels exploited there reportedly provided some of the richest gold-bearing concentrations ever discovered in California's Sierra Nevada district. From 1855 to 1871, for example, residents shipped some 60 million dollars' worth in gold from La Porte--a figure calculated at the historical price of roughly $20 per troy ounce. By 1857, Rabbit Diggings folks began to experience dissatisfaction with their original town name; sophistication had set in. It was time for a change, they decided. A leading citizen by the name of Frank Everts suggested La Porte as an alternative--never mind that Everts hailed from La Porte, Indiana--and La Porte was quickly agreed upon. For the next five years, through 1862, La Porte experienced classic boomtown commerce activity; loads of gold came pouring out of the hydraulic operations, and the auriferous gravels seemed practically inexhaustible. Unfortunately for La Porte's residents, the flush times couldn't last. Following the peak year of 1862, a gradual decline began, although as late as 1866 we find the citizens of La Porte embroiled in a spirited fight to secure the county seat of a proposed brand new California county called Alturus. Neither idea came to pass, though, and governmental officials eventually annexed La Porte to Plumas County, where it has remained ever since. In addition to its mind-boggling lucrative gold-bearing gravels, La Porte boasts yet another important historical distinction in the, at first blush, improbable area of skiing. As the story goes, deep winter snows in the region regularly blocked the trails, so miners, exercising creative ingenuity, began to fasten "Norwegian snowshoes" to their feet, permitting travel over frozen crusts. These hand-fashioned snow runners became de facto skis, and inevitably a rivalry developed to determine which "snowshoer" could ski the fastest. This in turn led to the formation of the Alturus Ski Club, an organization that scheduled downhill races for cash prizes. Perhaps it is bombastic braggadocio, but today La Porte, California, claims the title of being the "birthplace of competitive skiing." After exploring historic La Porte, it's of course time to get down to paleontological business. Once at the fossil locality in the vicinity of town--setting foot there with an intent to secure specimens only if the United States Forest Service continues to permit unauthorized fossil collecting (always check with local USFS rangers to determine the most recent rules and regulations)--you will observe a prominently precipitous cliff composed predominantly of brownish mudstones and shales, underlain by white to rust-tinged gold-bearing gravels. As observed from a distance, the relatively inconspicuous layer of greenish leaf-bearing upper Eocene La Porte Tuff occurs near the rim of this cliff which along with the auriferous gravel near the base was exposed by mid to late 1800s hydraulicking operations. At last field check, only a roughly 16 by 6 foot thick section of that once extensive, laterally continuous horizon of plant-yielding rhyodacite La Porte Tuff remains in its original stratigraphic position. Within the immediate confines of the abandoned hydraulic pit, obvious strewn accumulations of spent rocky rubble will be observed--the dramatic evidence of copious outwash derived from untold cubic yards of auriferous gravels washed away during decades of hydraulicking. Sometimes splinters and chunks of petrified wood can be spotted among the gravel debris below the cliff, fragmental remains of permineralized trees dislodged from the middle Eocene auriferous gravels by the great hydraulic monitors. Fortunately for seekers of paleobotanical adventure, those high-powered streams of water also undercut the fossil-bearing upper Eocene Porte Tuff layer near the rim of the cliff, causing rather common blocks of talus material to accumulate at the base. These blocks provide easy collecting. To reach the fossiliferous talus blocks, hike along the narrow erosion gully nearest the cliff. Be prepared, though, because this is sometimes a frustrating path; dense pockets of brush have claimed portions of the channel, creating natural obstacles to your progress. It's probably better to simply follow the erosion course from a safe distance, finally crossing the channel when you at last spot the large blocks of greenish fossil-bearing La Porte Tuff strewn along the base of the cliff for several hundred feet. This leaf-bearing volcanic ash is easily distinguished from the brownish mudstones and whitish quartz pebble-rich beds of auriferous gravel that comprise most of the cliff. Watch for the pale greenish, faintly stratified blocks lying against the lower slopes and at the foot of the cliff. The fossil leaves are locally quite abundant here, and are for the most part very well preserved. Evidently, the volcanic ash provided an excellent medium for the preservation of delicate organic vegetable tissues. Many fragmental fossils will likely be observed exposed on naturally eroded surfaces of the greenish tuff, and numerous chunks of material fractured off by previous collectors sometimes reveal profuse, albeit mainly imperfect plants. The best fossil leaves can be secured by patient and persistent cracking of the tuff with the blunt end of a traditional geology rock hammer; wear adequate eye protection at all times while doing so, of course--and don't use a wide blade roofer's implement, as advocated by any number of paleobotanists: It lacks the necessary mass, heft, to cleave with repeated precision such hard rock. Many, but certainly not all fossil leaves here lie at varying angles within the tuff, so it is difficult to prevent damaging superior specimens. Be sure to bring along a fast-drying glue, in order to mend breaks on the spot. The highly indurated tuff is easily glued back together, a blessing since in practical experience it is virtually impossible to collect here without fracturing several nice fossil leaves no matter how meticulous the method used. Wrap your specimens in tissue paper or paper towels; store the smaller samples in plastic sandwich bags for safe transporting back home. While exploring the paleobotanically productive abandoned hydraulic pit near La Porte, one notes that typical trees growing in the vicinity of the fossil site today constitute a dominantly coniferous association of Ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa), Sugar pine (Pinus lambertiana), Lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta), Jeffrey pine (Pinus jeffreyi), California red fir (Abies magnifica), Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), and Incense cedar (Calocedrus descurrens). But approximately 34.2 million years ago, that botanically pervasive gymnospermous component so famously identified with a modern montane Sierra Nevada environment did not exist. Paleobotanical material identified from the upper Eocene La Porte Tuff cumulatively includes a predominance of excellently preserved dicotyledonous leaves that bear a close botanic affinity to modern-day equivalents now indigenous to southern Mexico, Central America, parts of South America, southeastern China, and the Philippines. Climate during deposition of the La Porte Tuff was probably semi-tropical, with approximately 65 inches of rainfall per year and an average annual temperature of 75 degrees. All told, some 43 species of fossil plants have been secured from the long-abandoned hydraulic gold mine in the neighborhood of La Porte, Plumas County, northern Sierra Nevada, California. All specimens first studied by paleobotanist Susan S. Potbury in the 1930s occur in the fossiliferous volcanic ash bed--the upper Eocene La Porte Tuff--which has been dated through sophisticated radiometric methods at 34.2 nnillion years o1d. Fossil specimens identified by paleobotanist Susan S. Potbury in her monumental paleobotanical treatise The La Porte Flora Of Plumas County, California, originally issued November 25, 1935, include: 1) A fern of uncertain taxonomic affinity, referred to the form genus Polypolites (incertae sedis), first erected by Goppert in 1836; lots of fossil ferns have been placed into this catchall genus, usually because they resemble examples in the family Polypodiaceae, which contains about 50 genera and an estimated 550 mostly tropical species. 2) A cycad that Susan S. Potbury originally identified as Zamia mississippiensis; re-assigned (in 2012) to Dioonopsis macrophylla, a species probably similar to the living evergreen cycad Dioon edule--common name Chamal--that can grow to 13 feet. Ranges in natural habitat through Central America to Mexico (gulf area and northeast), preferring deciduous and oak forests at elevations from sea level to roughly 4,900 feet. 3) Cephalotaxus californica, a new species of yew (family Taxaceae) that Potbury in 1935 compared to the living Cephalotaxus argotaenia, the Chinese flowering yew, now known taxonomically as Amentotaxus argotaenia, a small tree or shrub that grows from six and a half to 23 feet high in China (Fujian, Gansu, Guangdong, Guangxi, Guizhou, Hubei, Hunan, Jiangsu, Jiangxi, Sichuan) and southeast Tibet. 4) Leaf rays from a new species of fossil palm Potbury named Sabalites rhapifolius; resembles a living Asiatic palm that Potubury called Rhapis flabilliformis, which is now know as Rhapis excelsa. Common names for it include: Large Lady Palm; Ground Rattan Cane; Broadleaf Lady Palm; Slender lady palm; Bamboo palm; Broad-leaved slender lady palm; Fern rhapis; Ground Rattan Palm; and Miniature fan palm. Native to southern China and Taiwan. It's a thicket forming fan palm, producing 13 by 13 foot-wide clumps that eventually become very dense. 5) Smilax goshenensis--the Eocene equivalent of the extant Smilax mexicana, synonym of Smilax spinosa. Common name greenbriar or Sarsparilla vine. In much of Mexico it's called Zarzaparrilla, though in Yuctan Maya it's referred to as Koke. Grows from sea level to elevations as high as 8,000 feet. Native to Belize, Bolivia, Brazil Northeast, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, French Guiana, Guatemala, Guyana, Honduras, Mexico Central, Mexico Gulf, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panamá, Peru, Southwest Caribbean, Suriname, Trinidad-Tobago, and Venezuela. 6) Chrysophyllum conforme--The Eocene analog of the living satinleaf Chrysophyllum mexicanum, an evergreen shrub or a tree with a spreading crown that grows up to 75 feet. It's indigenous to Panama, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Belize, Guatemala, and Mexico, preferring a moist to wet mixed forest; most commonly found at low elevations, though it can ascend to 5,600 feet. 7) Cinnamonum acrodromum--The Eocene counterpart of today's Kalingag, Cinnamonum mercadoi. Usually a small evergreen tree that grows from 20 to 33 feet high. It's native to the Philippines, where it grows best in forests at low and occasionally medium elevations to 6,600 feet. 8) Cinnamonum dilleri--The Eocene genus-species of the extant Japanese cinnamon Cinnamonum penduculatum, an evergreen tree that grows to roughly 32 to 49 feet; presently native to Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and eastern China (Anhui, Fujian, Sichuan, Jiangsu, Jiangxi, and Zhejiang). 9) Euphorbiaphyllum multiforum--A fossil species that most closely resembles the modern Drypetes alba (common name, cafeillo), an evergreen tree indigenous to Cuba, Puerto Rico, Domincan Republic, southern Florida, US Virgin Islands, Haiti, Jamaica, Leeward Is., and Windward Is. 10) Ficus goshenensis--An Eocene analog for the modern Ficus bonpandiana, synonymous with F. obtusifolia, an evergree tree that grows from sea level to 3,280 feet in Bolivia and Brazil, north through Central America to Mexico. Tolerates a wide range of environmental conditions, from very wet habitats to seasonally very dry areas; can grow to 148 feet tall. 11) Laurophyllum intermedium. A member of the laurel family that Susan S. Potbury equated with the modern evergreen Misanteca capitata (synonymous with Licaria capitata) whose common names include misateco, palo misateco, laurel of the sierra, black laurel, laurel canelillo de (Veracruz), hymnio moko, and xolimte. It's distributed from sea level to an elevation of around 1,968 in Mexico (Chiapas, Oaxaca, Puebla, San Luis Potosí, Tabasco, and Veracruz), Guatemala, Belize, and Honduras. 12) Laurophyllum ramiferivum: This is what paleobotanist Susan S. Potbury called the Eocene equivalent of an unspecified member of the genus Ocotea, a member of the laurel family; today the 300-some species of Ocotea are native to the Caribbean, West Indies, and tropical and subtropical areas of Africa, Madagascar, and the Mascarene Islands. 13) Leaf specimens that Susan S. Potbury called Cornus kelloggi, a presumably extinct species that has no known exact living counterpart. A dogwood, possibly akin to an extant species in southeast Asia. Early paleobotanists thought it resembled the living Pacific dogwood Cornus nuttalli. 14) Fossil leaves that paleobotanist Susan S. Potbury called Hyperbaena diforma, the Eocene analog of the living Hyperbaena smilacina, a member of the Moonseed family, several members of which contain the toxic alkaloid tubocurarine, used to prepare various forms of curare. Usually a twining woody vine, more rarely an upright shrub. Now native to Colombia, Costa Rica, and Nicaragua. 15) Paleobotanical material that Susan S. Potbury described as Styrax curatus, the Eocene variety of today's Styrax arengteus, sometimnes called Snowball. It's an evergreen tree usually topping out at around 65 feet, with occasional specimens to 98 feet. Harvested in the wild for an aromatic resin that is used locally. Ranges today from Panama to Mexico at elevations from roughly 300 to 5,577 feet. 16) Phyllites alchorneopsis--A form genus-species of uncertain botanic affinity (incertae sedis). It shows closest affinity to two modern members of the genus Alchornea--Alchornea trewiodes of southern China (notably in Guangxi) and north Vietnam and Alchornea davidii of southern China. 17) Tabernaemontana intermedia--The Eocene equivalent of the living Tabernaemontana lanceolata--common name Grape jasmine. An evergreen shrub or small tree that grows to one and half to 16 feet tall. Present native range is southern China, India, Myanmar, and Thailand. Grows at elevations from 330 to 5,250 feet in southern China. 18) Cissampelos rotundifolia--The Eocene analog of the living Cissampelos pareira, whose common name is Velvet-leaf (also known as Velvetleaf or Abuta), a climbing vine native to Aldabra, Andaman Is., Argentina, Aruba, Assam, Bahamas, Bangladesh, Belize, Bolivia, Borneo, Brazil North, Brazil, Cayman Is., China, Colombia, Comoros, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, East Himalaya, Ecuador, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Florida, French Guiana, Galápagos, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, India, Jamaica, Kenya, Laos, Leeward Is., Lesser Sunda Is., Madagascar, Maluku, Mauritius, Mexico, Mozambique, Myanmar, Netherlands Antilles, New Guinea, Nicaragua, Nicobar Is., Panamá, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Puerto Rico, Rwanda, Réunion, Somalia, Southwest Caribbean, Sri Lanka, Sulawesi, Suriname, Taiwan, Tanzania, Thailand, Trinidad-Tobago, Uganda, Uruguay, Venezuela, Venezuelan Antilles, West Himalaya, Windward Is., and Zimbabwe. 19 Leguminosites falcatum: The Eocene counterpart of the living Prioria copaifera, an evergreen tree that can grow to 164 feet. It ranges from Nicaragua to Colombia (also occurs in Jamaica), preferring tidal estuaries in the vicinity of the mangrove fringe. 20) Acalypha serrulata--The Eocene genus-species of the extant Acalypha schlechtendaliana. A member of the Euphorbia family; a shrub whose modern range is Madagascar, Reunion Island, and various Islands in the Indian Ocean (excluding the Seychelles). In Madagascar, it grows from sea level to 6,500 feet. 21) Persea pseudo-carolinensis--The Eocene equivalent of the modern Persea podandenia (synonymous with Persea liebmannii), an evergreen tree (member of the laurel family) now native to parts of Mexico (Chiapas, Chihuahua, Durango, Guanajuato, Guerrero, Hidalgo, Jalisco, Nuevo León, Oaxaca, Puebla, Querétaro, San Luis Potosí, Sonora, Tamaulipas, and Veracruz). Grows best in tropical deciduous and humid pine-oak forests at elevations between 1,900 and 5,900 feet. 22) Persea praelingue--The Eocene variety of Persea lingue, a member of the laurel family, native to Argentina and Chile. In Chile, it grows best in humid areas that receive almost constant rainfall; tolerates short dry periods of no longer than a month. In interior valleys and coastal mountains it grows at elevations from 1,600 to 6,000 feet. 23) Leaves that Susan S. Potbury assigned to Stercula ovata, the Eocene analog of the modern Sterculia lanceifolia, an evergreen small tree indigenous to southern China, Bangladesh, and northeast India. In China, it grows at elevations from 2,600 to 6,500 feet on forested slopes. 24) Specimens of Davilla rugosa, which is the Eocene genus-species of the living Davilla kunthii, a woody vine or small tree native to Belize, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, French Guiana, Guatemala, Guyana, Honduras, Mexico (central, gulf area, southeast, and southwest), Nicaragua, Panamá, Peru, southwest Caribbean, Suriname, Trinidad-Tobago, and Venezuela. Prefers a moist to wet hilly pine forest habitat at elevations of 1,150 to 1,500 feet. 25) Ilex oregona--The Eocene variety of Ilex paraguensis. Common name is Yerba mate. It's in the holly genus. A small evergreen tree that typically grows from 13 to 26 feet high. Presently found in Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Brazil. Can grow at elevations up to 4,900 feet. 26) A species that Susan S. Potberry assigned to Sophora respandifolia, a presumably extinct form whose leaves correspond to no known specific living plant; extant members of genus Sophoria (pea family) are native to southeast Europe, east Asia, tropical regions in Australia and the Pacific, western South America (Chile, Argentina and Juan Fernandez Is.), coastal Kenya south to South Africa and Madagascar, and coastal east Brazil. 27) Alangiophyllum petiocaulum: An extinct Eocene species that shows closest relationships to the modern Alangium chinese, a shrub or small tree that grows to about 11 and a half feet in forest margins and exposed areas below 8,200 feet in China (Anhui, Chongqing, Fujian, Gansu, Guangdong, Guangxi, Guizhou, Hainan, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Jiangsu, Jiangxi, Shanxi, Sichuan, Yunnan, and Zhejiang), Taiwan, south Tibet, Bhutan, India, Nepal, east Africa, and southeast Asia. 28) Phyllites laportiana--A form genus-species of uncertain taxonomic relationship (incertae sedis). Likely an extinct species. In studying the upper Eocene La Porte Flora, paleobotanist Susan S. Potbury concluded rather succinctly: "Thus far, no clues regarding its taxonomic affinities have been discovered." 29) Quercus nevadensis--The Eocene equivalent of the extant Lithocarpus corneus var. hainanensis, native to China (southern Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi, southern Guizhou, Hainan, southern Hunan and eastern Yunnan), Vietnam (northeast), and Taiwan; prefers elevations below 3.200 feet along sunny mountain slopes and drier areas in evergreen forests. 30) Petrea rotunda--The Eocene variety of Petrea volubilis, a vine in the Verbenaceae family; common names include purple wreath, queen's wreath, sandpaper vine, and nilmani. Native to Belize, Bolivia, Brazil (North, Northeast, South, Southeast, and West-Central), Cayman Is., Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Florida, French Guiana, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Leeward Is., Mexico (Central, Gulf, Northeast, Southeast, and Southwest), Nicaragua, Panamá, Paraguay, Peru, Puerto Rico, Suriname, Trinidad-Tobago, Venezuela, and Windward Is. 31) Leaf specimens that paleobotanist Susan S. Potbury described as Liquidamber californicum, the fossil variety of Liquidambar styraciflua--American sweetgum. Also known as American storax, hazel pine, bilsted, redgum, satin-walnut, star-leaved gum, alligatorwood, or sweetgum; a deciduous tree indigenous to Central America, north through Mexico to the southeastern United States. Natural habitats include swampy woods that are often inundated annually and moist to wet areas of mixed forest, mostly on mountain sides or along streams. In Guatamala, it's often associated with oak or pine at elevations from 2,900 to 6,900 feet. 32) Ocotea eocernus--This is what Susan S. Potbury called the Eocene genus-species of today's Ocotea cernua, also commonly referred to as Cayenne Rosewood, an evergreen tree that typically grows 16 to 32 feet tall, with occasional specimens pushing 64 feet. It's regularly harvested in the wild for its essential oil. Native to Brazil, Bolivia, the Caribbean, Central America, and Mexico. In Guatamala, it lives at or a little above sea level in a wet mixed forest. Costa Rica specimens prefer a lowland evergreen forest. In general, it's a plant of tropical areas at elevations from near sea level to over 4,900 feet. 33) Persea pseudo-carolinensis--Paleobotanist Susan S. Potbury believed that this fossil species, while obviously similar to the common living swampbay of the southeastern United States, was closer to the modern Mexican redbay (Persea podadenia--synonymous with Persea liebmannii), an evergreen tree (grows to 50 feet) in the laurel family endemic to Mexico (Chiapas, Chihuahua, Durango, Guanajuato, Guerrero, Hidalgo, Jalisco, Nuevo León, Oaxaca, Puebla, Querétaro, San Luis Potosí, Sonora, Tamaulipas, and Veracruz). It regularly grows in tropical decicuous and humid pine-oak forests at elevations from 1,900 to 2,600 feet. 34) Sturculia ovata--The Eocene equivalent of the living Stercolia lanceifolia, an evergreen shrub or small tree whose seed is sometimes harvested from the wild as a local food source. It's endemic to southern China, Bangladesh, and northeast India. 35) Quercus suborbicularia--A fossil species whose leaves match no living plant, though Susan S. Potbury found its closest contemporary counterpart in the white oak Quercus durangensis (synonymous with Quercus rugosa), endemic to Mexico (Aguascalientes, Baja California, Chihuahua, Coahuila, Durango, Guanajuato, Hidalgo, Jalisco, Michoacan, Oaxaca, Sinaloa, Puebla, San Luis Potosi, Sonora, Tamaulipas, Tlaxcala, Veracruz, and Zacatecas), southern Arizona, and Guatemala at elevations of 3,900 to 10,500 feet. 36) Ulmus pseudo-fulva--The Eocene analog for the living Mexican elm Ulmus mexicana (also called Membrillo) a deciduous tree that normally grows 32 to 82 feet tall (though some specimens can reach over 250 feet). It's sometimes harvested in the wild for medicinal use and a source of wood. Indigenous to Panama north to Mexico at elevations of 2,950 to 8,850 feet. 37 Aleurites americana--The Eocene variety of the modern Candlenut (also called Kuku Nut) Aleurites triloba, synonymous with Aleurites moluccanus, an evergreen tree that grows up to 98 feet. Endemic to China, India, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, Philippines, New Guinea, Australia, and Pacific Islands in rain or monsoon forests at altitudes below 3,900 feet where mean annual temperatures range from 64 to 82 degrees Fahrenheit and the average annual rainfall is 26 to 170 inches. 38) Columbia occidentalis--The Eocene counterpart for the extant Columbia longipetiolata (a synonym of Colona longipetiolata), a member of the mallow family (subfamily Grewioideae). Indigenous to the Philippines. 39) Lonchocarpus coriaceus--This is what paleobotanist Susan S. Potbury called the Eocene genus-species of the living Lonchocarpus hondurensis, an evergreen tree that usually grows 19 to 26 feet tall, though occasional specimens can reach 38 feet. Develops a deciduous habit when growing in areas that experience a long dry season. Endemic from Honduras to Mexico at elevations up to 1,300 feet. 40) Meliosma goshenensis--The Eocene variety of the modern Meliosma panamensis (synonymous with Meliosma glabrata), an evergreen tree native to Bolivia, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Honduras, Mexico Gulf, Mexico Southwest, Nicaragua, Panamá, and Peru. A member of the family Sabiaceae. 41) Microdesmis occidentalis--Susan S. Potbury matched fossil leaves from this species to the extant Microdesmis casearifolia, an evergreen tree that typically grows from 49 to 98 feet high It's native to China, Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines, where it prefers rainforests and mixed deciduous forests at elevations from 32 to 2,600 feet. 42) Mimosites acutifolius--An Eocene species analogous to the present-day Pithecellobium corymbosum (a synonym of Hydrochorea corymbosa), often called a blackbead, a member of the legume family that is indigenous to Bolivia, Brazil North, Brazil Northeast, Brazil West-Central, Colombia, Ecuador, French Guiana, Guyana, Peru, Suriname, and Venezuela. In Bolivia, it prefers the rainforest vegetation zone and savannas of southern Beni and Yungus to elevations of 4,900 feet. 43) Rhamnidium chaneyi--Paleobotanist Susan S. Potbury assigned leaves from this Eocene species to the living Saguaraji, Rhamnidium elaeocarpum, a deciduous tree that can grow 26 to 62 feet high in its native lands of Argentina, Paraguay, Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, and Ecuador. Prefers a tropical rainforest habitat or a savanna at altitudes between 492 and 3,940 feet. Within the paleobotanically significant upper Eocene La Porte Tuff, those 43 species of fossil plants probably accumulated in reworked volcanic material re-deposited in a sluggish stream. This conclusion is based partly on the observation that the tuff frequently displays consistent evidence of well-defined bedding, and while some of the locally abundant leaves embedded in the rhyodacite tuff lie at random angles (ostensibly suggesting rapid entombment), a majority of specimens do not; they reside along distinct, cleavable bedding planes, signifying a more gradual mode of sedimentary accumulation, where eroding volcanic detritus eventually became re-deposited (re-purposed, as it were) in the river channel that had incised the older middle Eocene shales and auriferous gravels that lie with disconformable relations below the La Porte Tuff. In other words, for example, the upper Eocene La Porte Tuff does not represent a lahar deposit. Part of the entire "La Porte problem," in a broader scientific context, is that nobody can actually correlate the upper Eocene La Porte Tuff with any known late Eocene to lower Oligocene volcanic tuff or ignimbrite deposit presently exposed in either neighboring Nevada or the Sierra Nevada; videlicet, it just doesn't fit mineralogically with any other known volcanic event. Some geologists speculate that it could be related to documented late Eocene extrusives in the Cascade physiographic region. At any rate, the geologic evidence suggests that the La Porte Tuff accumulated in a stream, mainly as re-deposited water-laid rhyodacitic ash reworked from volcanic exposures--now long eroded away--that postdate incision of the 45 million year-old middle Eocene shales that lie below the La Porte Tuff. Probably an initial pyroclastic impulse choked the ancient stream channel, instantaneously entombing many leaf specimens at varying angles within the volcanic fallout; eventually, though, the brief explosive activity ceased, after which rather rapid erosion processes continued to supply the channel with profuse quantities of poorly consolidated ash piled high in the immediate vicinity of the watercourse. The re-deposited volcanic detritus now settled out in the stream bed, along with minor muddy constituents, ultimately capturing within several feet of regularly bedded layers innumerable leaves and other botanic structures, now preserved in exquisite detail. In addition to late Eocene leaves in the blocks of La Porte Tuff along the foot of the cliff, the brownish shales which comprise most of the cliff face itself are also fossiliferous. Nicely preserved plant impressions of semi-tropical vegetation are locally common, as are chunks of carbonized wood--not petrified, or permineralized, but rather more like a substance well on its way to becoming coal. The plant-bearing shales represent a middle Eocene age, approximately 45 million years old, correlated stratigraphically with the paleobotanically remarkable Chalk Bluffs Flora (contains 70 species of plants) found at numerous abandoned hydraulic gold mines distributed throughout California's northern Mother Lode Country. The shales conformably overlie the middle Eocene auriferous gravels and were no doubt laid down in stagnant bodies of water and oxbow lakes which came into existence along the extensive floodplains of rivers that only a few millions of years earlier had deposited vast fortunes in gold. Not only is the fossiliferous La Porte Tuff and shale sequence worthy of exploration, but the underlying auriferous gravel is obviously a very interesting subject, too. Of course, the term "auriferous gravel" is not a formally accepted geologic formation name. It has no strict nomenclatural significance because there are other gold-bearing gravels in California's Mother Lode country of different age. But, through long usage and tacit acceptance by local California geologists, the term has come to connote a very specific rock deposit. The auriferous gravels of the northern Sierra Nevada likely accumulated approximately 48 to 38 million years ago during the Eocene Epoch of the Cenozoic Era. Based on the available geologic evidence, the gravels were deposited along the floodplains of aggrading streams--that is, watercourses which were building up sediments instead of eroding their channels. Most of the gold recovered by hydraulic methods came from the so-called "inner channel" of the auriferous gravel, a relatively narrow zone only several feet deep and tens of feet wide situated at the base of the gravels, near bedrock. Above the inner channel, or "blue ground"--as the miners referred to this unbelievably rich zone--younger gravels accumulated to a thickness of 400 feet. These "bench gravels" were usually impoverished in gold, although there were a few localities of record where it was abundant. As the bench gravels slowly accumulated in the valleys, giant floodplains developed and the rivers began to create great anastomosing patterns. The surrounding countryside was covered with a lush semi-tropical vegetation similar to that of present-day southern Mexico, Central America, and parts of South America. One of the more enduring mysteries confronting geologists who have studied the auriferous gravel is why would rivers, after having eroded their channels for millions of years, suddenly begin to aggrade, or build up sediments? Among several possible explanations proposed by not a few investigators, a model developed by the late geologist Cordell Durrell provided the first eminently reasonable working hypothesis. Durrell suggested that a change of climate from one of regular wet and dry seasons to one of irregular wet and wetter seasons could have triggered catastrophic flooding, much like that which occurs today in the vicinity of Rio De Janeiro, Brazil, a region with vegetation and a climate similar to that inferred for the Sierra Nevada some 45 million years ago. Such floods are very local, of course, but Durrell pointed out that no single flood need cover a large area to account for the accumulation of auriferous gravel. All that was needed was to have a sufficient number of floods cover every part of the region where auriferous gravels now occur--in other words, the 10 northern counties of the Sierra Nevada or an area of roughly 12,000 square miles. At first, this night seem to represent a prohibitively extensive area for floods to affect. But consider Durrell's calculations. Deposition of the auriferous gravel probably lasted for as long as 10 million years. or most of the middle Eocene. Therefore, there was ample time for periodic flooding to account for the gold-bearing gravels. Durrell suggested that if only one catastrophic flood occurred every 50 years, there could have been as many as 200,000 floods. If the rain gods were more generous and the figure was more like one flood every 20 years, then the total climbs to a possible 500,000 floods. Now, Durrell introduces us to some basic arithmetic. Suppose each flood deposited an average of only two feet of sediment affecting an area of 10 square miles (an extremely conservative estimate, to be certain). That would mean that it would require 250,000 floods to bury the 10 northern counties of the Sierra Nevada to a depth of 400 feet, the actual measured thickness of the auriferous gravel we see today in northern California. A second intriguing idea, championed by the late paleobotanist Howard Schorn (former collections manager of fossil plants at the University California Museum of Paleontology) and others, proposes that roughly 48 to 45 million years ago a major eastward marine transgression into the proto-Great Central Valley area backed up westward-draining watercourses in the ancestral western Sierra Nevada, creating hydrological conditions conducive to an aggrading depositional environment that introduced gold enrichment to the sedimentary system. Yet a third explanation--advocated by a number of geologists---postulates that several highly resistant Paleozoic and Mesozoic metamorphic ridges (so-called "greenstone and greenschist barriers") acted as impedimentary obstacles to most westward draining Eocene rivers, creating natural geographic constriction points behind which waters began to "dam," initiating a vast system of braided streams that eventually began to aggrade. Of course, as fascinating as the geological mechanics of aggrading rivers is, an inevitable question comes to mind: Just how much gold remains within the auriferous gravel? Nobody's really certain, but there is justifiable cause for pessimism. Very little of the gold-rich inner channel was left unexploited during the reign of hydraulic mining. Also, those portions of that fabulous bonanza deposit not amenable to profitable hydraulicking were cleverly gleaned of gold by traditional tunneling methods (where for instance the inner channel was buried too deeply). The inevitable conclusion is that prospective prospectors are likely to be disappointed when they find that the inner channel has been all but exhausted of its supply of gold. And while extensive exposures of overlying bench gravels remain undisturbed, left in place when the last hydraulickers walked away from their diggings in the mid 1880s, uniformly inferior gold content in strata above the once unimaginably rich inner channel certainly precludes a profitable mining enterprise--even if one could theoretically secure the necessary environmental permits. Still, some questions remain concerning the gold contained in the auriferous gravel. For one, where did it come from? A general consensus is that most of the aurum that accumulated in the inner channel came from gold-bearing quartz veins in metamorphic rocks that outcropped within the regional hydrologic cachment of the ancestral northern Sierra Nevada. The gold was likely released from the veins by an extended period of weathering which preceded deposition of the auriferous gravel. Although locally significant amounts of gold occurred in the overlying bench gravel, the overall concentrations were far inferior to those of the inner channel. Yet, the fact that it did contain quantities of gold is important to note, because up to twenty percent of the bench gravel definitely came from sources well east of the Eocene Sierra Nevada area. This suggests that at least some of the auriferous gravel gold was delivered by watercourses whose headwaters existed in what's now present-day Nevada. And that leads to the rather fascinating paleogeographical observation that some 45 million years ago, during deposition of the auriferous gravels, Nevada was roughly half as wide as it is today--in other words instead of 322 miles, only about 161 across. Then too, at that moment in middle Eocene geologic time, the regional geographic divide, presently situated in the Sierra Nevada at Echo Summit (west of which watercourses run toward the Pacific Ocean), likely resided in the vicinity of Austin, central Nevada. Why Nevada experienced a geophysical inflation is due to extensional processes associated with creation of the Basin And Range physiographic province. Approximately 20 million years ago, potent Earth forces associated with upwelling magmas and crustal thinning began to stretch and pry apart the Miocene Nevadaplano--a ramp-like plateau of gradually increasing elevation that reached eastward from the ancestral Sierra Nevada--forcing nascent Nevada to expand to twice its previous width while, simultaneously, causing numerous parallel north-south trending block faulted mountain ranges (horsts), bounded by valleys (grabens), to develop perpendicular to the direction of crustal thinning precipitated by a subduction zone that had passed beneath the pre-Basin And Range territory. By 6.8 million years ago, Basin And Range elevations had dropped to approximate those observed today. Today, La Porte is a scenic little vacation/resort community in the northern Sierra Nevada. But during the Gold Rush days of the mid 1800s it was a rollicking hydraulicking town whose citizens extracted millions of dollars worth in gold from the auriferous gravels. At a locality in the vicinity of La Porte, the hydraulickers also uncovered another kind of treasure--fossil plants, which tell of a time when the present-day gymnospermous conifer-rich Sierra Nevada scene resembled a subtropical forest in Mexico, Central America, South America, southern China, and the Philippines; a time when a violent volcanic eruption devastated the land, when skyward-flung searing ash fell back to Earth to accumulate in a stream that had incised a channel into underlying 45 million year-old plant-bearing shales. Not long after, additional rhyodacitic ash gradually began to erode into the watercourse, where constant currents substantially reworked the volcanic constituents to form a re-deposited water-laid tuff, the La Porte Tuff, whose original slushy layers, lithified over several million years by geologic forces of heat and pressure, preserved in extraordinary detail the kinds of plant life which once thrived here some 34.2 million years ago--great quantities of leaves and associated botanic structures shed from shrubs, trees, and vines that bordered the late Eocene stream. Yet, had it not been for hydraulic mining during the gold rush days of the 1800s, the fossils might have had to wait millions of additional years for the powers of natural erosion to expose them to the light of day. Now, at the rim of a crumbling water-blasted cliff, lies a bed of hardened ashy sludge, within which occurs direct evidence of a great subtropical forest that contrasts dramatically with today's dominant conifer association of Ponderosa pine and Incense cedar and Douglas-fir--a late Eocene scene of Chinese Broadleaf Lady palm, ferns, Mexican cycads, Chinese flowering yew, liquidamber/sweetgum, Moonseed, Sarsparilla vine, satinleaf, cinnamon trees, fig trees, laurel trees, cafeillo, dogwood, Snowball, grape jasmine, Velvet-leaf, Yerba mate hollies, Asian stone oak, purple wreath, Cayenne Rosewood, Mexican redbay, Mexican white oak, Mexican elm, Candlenut, blackbead trees and Saguaraji, among others. Fossil plants and gold--both are products of a distant geologic age, and both treasures lie side by side at La Porte in Plumas County, northern Sierra Nevada. |

|

|

|

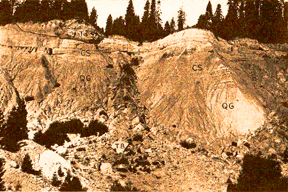

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--A portion of main street in La Porte, California, elevation roughly 5,000 feet, Sierra Nevada, California--staging area for the fabulous plant fossils at an abandoned hydraulic gold mine in the general vicinity of town. A Google Earth street car perspective that I edited and processed through photoshop. Right--A vintage circa 1935 photograph of the plant-bearing section exposed at an abandoned hydraulic gold mine in the neighborhood of La Porte, Sierra Nevada, California. Letters (in black) on photograph represent the following: T--the upper Eocene leaf-bearing La Porte Tuff exposed at the rim; CS--the middle Eocene leaf and carbonized wood-bearing shales which disconformably underlie the La Porte Tuff; QG--the middle Eocene auriferous gravels (gold-bearing) that underlie the shales and La Porte Tuff. Photograph courtesy Susan S. Potbury, from her publication The La Porte Flora Of Plumas County, California, originally issued November 25, 1935; contained in Carnegie Institute of Washington Publication 465, 1937, Eocene Flora Of Western America. I edited and processed it through photoshop. Note--Always check with the US Forest Service to determine if unauthorized fossil collecting is allowed at the La Porte locality. |

|

|

|

|

Left to right: On-site at the La Porte hydraulic gold mine, situated in the vicinity of La Porte, Sierra Nevada, California. Seekers of paleobotanical adventure investigate blocks of leaf-bearing upper Eocene La Porte Tuff (dated by radiometric methods at 34.2 million years old) that have fallen from the rim of the great hydraulic pit. Photographs originally taken with a Minolta 35mm camera. Note--Always check with the US Forest Service to determine if unauthorized fossil collecting is allowed at the La Porte locality. |

|

|

|

Left and right--Views of an abandoned hydraulic gold mine in the vicinity of La Porte, Sierra Nevada, California. The leaf-bearing upper Eocene La Porte Tuff (dated through sophisticated radiometric methods at 34.2 million years old) is the pale greenish layer at the rim; it yields some 43 species of of plants, most of whose closest modern-day counterparts live in southern Mexico, Central America, parts of South America, southeastern China, and the Philippines. Image at right clearly shows the stratigraphic relationship between the leaf-bearing, pale greenish late Eocene La Porte Tuff at the rim and the disconformably underlying plant-yielding middle Eocene brownish shales below. Photographs courtesy Larry Garside. I edited and processed them through photoshop. Note--Always check with the US Forest Service to determine if unauthorized fossil collecting is allowed at the La Porte locality. |

|

|

|

|

Left to right--Plant fossils from an abandoned hydraulic gold mine in the neighborhood of La Porte, Sierra Nevada, California. Left--A leaf fossil from the upper Eocene La Porte Tuff. Seems to most closely resemble what Susan S. Potbury called Cornus kelloggi, a presumably extinct species that has no known exact living counterpart. A dogwood, possibly akin to an extant species in southeast Asia. Early paleobotanists thought it resembled the living Pacific Dogwood Cornus nuttalli. Middle--Two fossil leaves exposed by natural erosion on the surface of a block of upper Eocene La Porte Tuff. Specimen at left is most similar to what paleobotanist Susan S. Potbury called Hyperbaena diforma, the Eocene analog of the living Hyperbaena smilacina, a member of the Moonseed family, several members of which contain the toxic alkaloid Tubacvurarine, used to prepare various forms of curara. Usually a twining woody vine, more rarely an upright shrub. Now native to Colombia, Costa Rica, and Nicaragua. Leaf at right looks a lot like what Susan S. Potbury described as Styrax curatus, the Eocene variety of today's Styrax arengteus, sometimnes called Snowball. It's an evergreen tree usually topping out at around 65 feet, with occasional specimens to 98 feet. Harvested in the wild for an aromatic resin that is used locally. Ranges today from Panama to Mexico at elevations from roughly 300 to 5,577 feet. Right--A chunk of carbonized wood (not petrified, or permineralized) from the middle Eocene shales that disconformably underlie the upper Eocene La Porte Tuff. Genus-species indeterminate. Note US nickel for scale (0.835 inch, 21.21 mm in diameter). Photographs originally taken with a Minolta 35mm camera. Note--Always check with the US Forest Service to determine if unauthorized fossil collecting is allowed at the La Porte locality. |

|

|

|

|

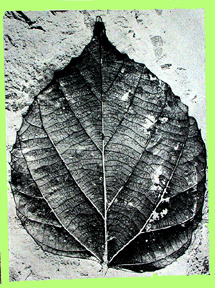

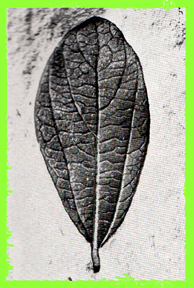

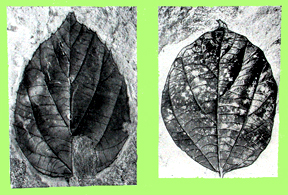

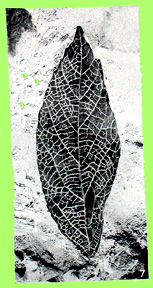

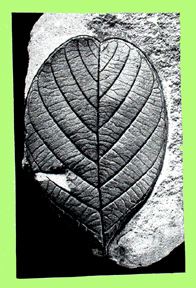

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right--Fossil leaves from the upper Eocene La Porte Tuff, secured from an abandoned hydraulic gold mine in the vicinity of La Porte, Sierra Nevada, California. Left--Laurophyllum ramiferivum: A member of the laurel family. This is what paleobotanist Susan S. Potbury called the Eocene equivalent of an unspecified member of the genus Ocotea; today the 300-some species of Ocotea are native primarily to the Caribbean, West Indies, tropical and subtropical areas of Africa, Madagascar, and the Mascarene Islands. Middle--Phyllites alchorneopsis--A form genus-species of uncertain botanic affinity (Incertae sedis). It shows closest affinity to two modern members of the genus Alchornea--Alchornea trewiodes of southern China (notably in Guangxi) and north Vietnam and Alchornea davidii of southern China. Right--Cinnamonum dilleri--The Eocene counterpart of the extant Cinnamonum penduculatum--commonly known as Japanese cinnamon, an evergreen tree that grows to roughly 49 feet; presently native to Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and eastern China. Photographs courtesy Susan S. Potbury, from her publication The La Porte Flora Of Plumas County, California, originally issued November 25, 1935; contained in Carnegie Institute of Washington Publication 465, 1937, Eocene Flora Of Western America. I edited and processed the images through photoshop; adding the green border, for one. Note--Always check with the US Forest Service to determine if unauthorized fossil collecting is allowed at the La Porte locality. |

|

|

|

|

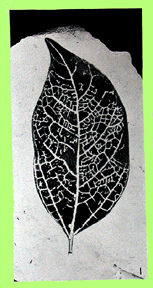

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right--Fossil leaves from the upper Eocene La Porte Tuff, secured from an abandoned hydraulic gold mine in the vicinity of La Porte, Sierra Nevada, California. Left--Tabernaemontana intermedia, the Eocene equivalent of the living Tabernaemontana lanceolata--common name Grape jasmine. An evergreen shrub or small tree that grows from about one and half to 16 feet tall. Present native range is southern China, India, Myanmar, and Thailand. Grows at elevations from 330 to 5,250 feet in southern China. Middle--Left and right: Phylittes alchorneopsis--A form genus-species of uncertain botanic affinity (Incertae sedis). It shows closest affinity to two modern members of the genus Alchornea--Alchornea trewiodes of southern China (notably in Guangxi) and north Vietnam and Alchornea davidii of southern China. Right--Ficus goshenensis: An Eocene analog for the modern Ficus bonpandiana syn. obtusifolia, an evergree tree that grows from sea level to 3,280 feet in Bolivia and Brazil, north through Central America to Mexico. Tolerates a wide range of environmental conditions, from very wet habitats to seasonally very dry areas. Photographs courtesy Susan S. Potbury, from her publication The La Porte Flora Of Plumas County, California, originally issued November 25, 1935; contained in Carnegie Institute of Washington Publication 465, 1937, Eocene Flora Of Western America. I edited and processed the images through photoshop; adding the green border, for one. Note--Always check with the US Forest Service to determine if unauthorized fossil collecting is allowed at the La Porte locality. |

|

|

|

|

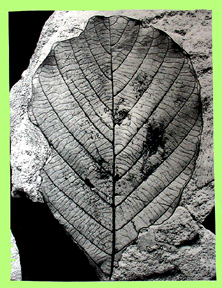

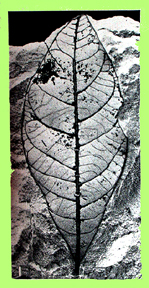

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right--Fossil leaves from the upper Eocene La Porte Tuff, secured from an abandoned hydraulic gold mine in the vicinity of La Porte, Sierra Nevada, California. Left--Cinnamonum acrodromum: The Eocene counterpart of the extant Cinnamonum mercadoi--common name Kalingag, a small evergreen tree that is native solely to the Philippines. Usually grows at elevations of 980 to 2,300 feet, but can ascend to an altitude of about 6,600 feet. Middle--Cissampelos rotundifolia: The Eocene analog of the living Cissampelos pareira, whose common name is Velvet-leaf (also known as Velvetleaf or Abuta), a climbing vine native to Aldabra, Andaman Is., Argentina, Aruba, Assam, Bahamas, Bangladesh, Belize, Bolivia, Borneo, Brazil North, Brazil, Cayman Is., China, Colombia, Comoros, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, East Himalaya, Ecuador, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Florida, French Guiana, Galápagos, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, India, Jamaica, Kenya, Laos, Leeward Is., Lesser Sunda Is., Madagascar, Maluku, Mauritius, Mexico, Mozambique, Myanmar, Netherlands Antilles, New Guinea, Nicaragua, Nicobar Is., Panamá, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Puerto Rico, Rwanda, Réunion, Somalia, Southwest Caribbean, Sri Lanka, Sulawesi, Suriname, Taiwan, Tanzania, Thailand, Trinidad-Tobago, Uganda, Uruguay, Venezuela, Venezuelan Antilles, West Himalaya, Windward Is., and Zimbabwe. Right--Leguminosites falcatum: The Eocene equivalent of the living Prioria copaifera, an evergreen tree that can grow to 164 feet high. It ranges from Nicaragua to Colombia (also occurs in Jamaica), preferring tidal estuaries in the vicinity of the mangrove fringe. Photographs courtesy Susan S. Potbury, from her publication The La Porte Flora Of Plumas County, California, originally issued November 25, 1935; contained in Carnegie Institute of Washington Publication 465, 1937, Eocene Flora Of Western America. I edited and processed the images through photoshop; adding the green border, for one. Note--Always check with the US Forest Service to determine if unauthorized fossil collecting is allowed at the La Porte locality. |

|

|

|

|

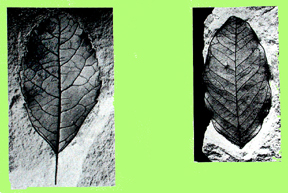

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right--Fossil leaves from the upper Eocene La Porte Tuff, secured from an abandoned hydraulic gold mine in the vicinity of La Porte, Sierra Nevada, California. Left--Acalypha serrulata: The Eocene genus-species of the extant Acalypha schlechtendaliana. A member of the Euphorbia family; a shrub whose modern range is Madagascar, Reunion Island, and various Islands in the Indian Ocean (excluding the Seychelles). In Madagascar, it grows from sea level to 6,500 feet. Middle--Left to right: Persea pseudo-carolinensis and Persea praelingue (both are members of the laurel family). The former is the Eocene counterpart to the modern Persea podandenia (synonymous with Persea liebmannii), an evergreen tree now native to parts of Mexico (Chiapas, Chihuahua, Durango, Guanajuato, Guerrero, Hidalgo, Jalisco, Nuevo León, Oaxaca, Puebla, Querétaro, San Luis Potosí, Sonora, Tamaulipas, and Veracruz). Grows best in tropical deciduous and humid pine-oak forests at elevations between 1,900 and 5,900 feet. Persea praelingue is the Eocene variety of Persea lingue, now native to Argentina and Chile. In Chile, it grows best in humid areas that receive almost constant rainfall; tolerates short dry periods of no longer than a month. In interior valleys and coastal mountains it grows at elevations from 1,600 to 6,000 feet. Right--Stercula ovata: The Eocene analog of the modern Sterculia lanceifolia, an evergreen small tree that presently lives in-southern China, Bangladesh, and northeast India. In China, it grows at elevations from 2,600 to 6,500 feet on forested slopes. Photographs courtesy Susan S. Potbury, from her publication The La Porte Flora Of Plumas County, California, originally issued November 25, 1935; contained in Carnegie Institute of Washington Publication 465, 1937, Eocene Flora Of Western America. I edited and processed the images through photoshop; adding the green border, for one. Note--Always check with the US Forest Service to determine if unauthorized fossil collecting is allowed at the La Porte locality. |

|

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right--Fossil leaves from the upper Eocene La Porte Tuff, secured from an abandoned hydraulic gold mine in the vicinity of La Porte, Sierra Nevada, California. Left and far right--Specimens of Davilla rugosa, the Eocene genus-species of the living Davilla kunthii, which is a woody vine or small tree now native to Belize, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, French Guiana, Guatemala, Guyana, Honduras, Mexico (central, gulf area, southeast, and southwest), Nicaragua, Panamá, Peru, southwest Caribbean, Suriname, Trinidad-Tobago, and Venezuela. Prefers a moist to wet hilly pine forest habitat at elevations of 1,150 to 1,500 feet. Middle--Left to right: Ilex oregona and Sophora respandifolia: The Eocene varieties of Ilex paraguensis and Sophora sp., respectively. Common name for Ilex paraguensis is Yerba mate. In the holly genus. A small evergreen tree that typically grows from 13 to 26 feet high. Presently found in Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Brazil. Can grow at elevations up to 4,900 feet. Sophora respandifolia corresponds to no known specific living plant, but extant members of genus Sophoria (pea family) are native to southeast Europe, east Asia, tropical regions in Australia and the Pacific, western South America (Chile, Argentina and Juan Fernandez Is.), coastal Kenya south to South Africa and Madagascar, and coastal east Brazil. Photographs courtesy Susan S. Potbury, from her publication The La Porte Flora Of Plumas County, California, originally issued November 25, 1935; contained in Carnegie Institute of Washington Publication 465, 1937, Eocene Flora Of Western America. I edited and processed the images through photoshop; adding the green border, for one. Note--Always check with the US Forest Service to determine if unauthorized fossil collecting is allowed at the La Porte locality. |

|

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right--Fossil leaves from the upper Eocene La Porte Tuff, secured from an abandoned hydraulic gold mine in the vicinity of La Porte, Sierra Nevada, California. Left--Tabernaemontana intermedia, the Eocene equivalent of the living Tabernaemontana lanceolata--common name Grape jasmine. An evergreen shrub or small tree that grows from about one and half to 16 feet tall. Present native range is southern China, India, Myanmar, and Thailand. Grows at elevations from 330 to 5,250 feet in southern China. Middle--Alangiophyllum petiocaulum: A presumably extinct Eocene species that shows closest relationships to the modern Alangium chinese, a shrub or small trees that grows to about 11 and a half feet in forest margins and exposed areas below 8,200 feet in China (Anhui, Chongqing, Fujian, Gansu, Guangdong, Guangxi, Guizhou, Hainan, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Jiangsu, Jiangxi, Shanxi, Sichuan, Yunnan, and Zhejiang), Taiwan, south Tibet, Bhutan, India, Nepal, east Africa, and southeast Asia. Right--Phyllites laportiana: A form genus-species of uncertain taxonomic relationship (Incertae sedis). Presumably an extinct species. In studying the upper Eocene La Porte Flora, paleobotanist Susan S. Potbury concluded rather succinctly: "Thus far, no clues regarding its taxonomic affinities have been discovered." Photographs courtesy Susan S. Potbury, from her publication The La Porte Flora Of Plumas County, California, originally issued November 25, 1935; contained in Carnegie Institute of Washington Publication 465, 1937, Eocene Flora Of Western America. I edited and processed the images through photoshop; adding the green border, for one. Note--Always check with the US Forest Service to determine if unauthorized fossil collecting is allowed at the La Porte locality. |

|

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right--Fossil leaves from the upper Eocene La Porte Tuff, secured from an abandoned hydraulic gold mine in the vicinity of La Porte, Sierra Nevada, California. Left and middle--Quercus nevadensis: The Eocene equivalent of the extant Lithocarpus corneus var. hainanensis, native to China (southern Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi, southern Guizhou, Hainan, southern Hunan and eastern Yunnan), Vietnam (northeast), and Taiwan; prefers elevations below 3.200 feet along sunny mountain slopes and drier areas in evergreen forests. Right--Petrea rotunda: The Eocene variety of Petrea volubilis, a vine in the Verbenaceae family; common names include purple wreath, queen's wreath, sandpaper vine, and nilmani. Native to Belize, Bolivia, Brazil (North, Northeast, South, Southeast, and West-Central), Cayman Is., Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Florida, French Guiana, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Leeward Is., Mexico (Central, Gulf, Northeast, Southeast, and Southwest), Nicaragua, Panamá, Paraguay, Peru, Puerto Rico, Suriname, Trinidad-Tobago, Venezuela, Windward Is. Photographs courtesy Susan S. Potbury, from her publication The La Porte Flora Of Plumas County, California, originally issued November 25, 1935; contained in Carnegie Institute of Washington Publication 465, 1937, Eocene Flora Of Western America. I edited and processed the images through photoshop; adding thr green border, for one. Note--Always check with the US Forest Service to determine if unauthorized fossil collecting is allowed at the La Porte locality. |

|