|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Those who would like to combine a trip to California's High Sierra Nevada wilderness with a visit to a fossil plant locality just might want to try the Mount Reba area of Alpine County. Here is a leaf-bearing site that dates from the late Miocene epoch, approximately 7 million years old. Some 14 species of ancient plants have been identified from the sedimentary-volcanic stratigraphic section of the Disaster Peak Formation, including specimens of cypress, Douglas-fir, evergreen live oak, tanbark oak, willow, and giant sequoia. Today, the fossiliferous rocks lie at an elevation of 8,640 feet, but the plants preserved in them prove that 7 million years ago the site of deposition in that specific sector of the Sierra Nevada could not have been any higher than about 2,500 feet. This so-called Mount Reba Flora thus demonstrates that at least a lengthy segment of the central to southern Sierra Nevada has been uplifted thousands of feet by geologic forces during the past 7 million years, although sophisticated geophysical studies of regional rates of erosion and plate tectonics suggest that most of that mountain building has happened over the past three million years; on the other hand, rather recently amassed evidence indicates that the northern Sierra Nevada sector has apparently remained at approximately the same elevations seen today for at least 50 million years. While the fossil locality is not difficult to find, be forewarned that a reliable four-wheel drive vehicle is required to reach the late Miocene botanic association. The "final assault" to the site is made along a rocky, rutty, and at times incredibly steep dirt path impassable in conventional vehicles. But the ultimate reward of such breathtaking High Sierran country, in addition to the opportunity to find some paleobotanically significant fossil leaves and petrified wood, is definitely worth the effort. Of course, prior to any excursion to the Mount Reba locality, always check with the local United States Forest Service officials to determine changes in collecting status. A convenient place to begin a journey to the fossil-bearing site is Angels Camp in Calaveras County, along historic State Route 49. This is justifiably one of the more famous of the old gold mining communities in the Mother Lode, western Sierra foothills. In addition to sightseeing and souvenir hunting, a main attraction at Angels Camp is the yearly encounter with frogs. The humorous Mark Twain short story "The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County" (1865)--inspired by a story Mr. Clemens had heard in Angels Camp while spending 88 days in California's Gold Country during the winter of 1864-'65 (most of that time in a cabin at Jackass Hill, about 6 miles southeast of Angels Camp; from January 22 to February 23, 1865, Twain resided in Angels Camp)--is commemorated each year here with a jumping-frog contest, a traditional event that has had its share of unusual turns. A number of years ago, for example, an ambitious individual keen on competition imported several two-and-a-half-foot-long carnivorous frogs from Africa and decided to enter them in the contest. Straight away, though, a regular shouting match broke out among the organizers over whether the monstrous amphibians should be permitted to compete. It was generally feared the African type would escape captivity and proceed to devour its smaller and less-aggressive cousins. Apparently siding with the alarmists, the California Department of Fish and Game initially would not even allow the man to bring his frog-whoppers into the Golden State. But regulations were eventually relaxed. Not only did the amazing amphibians find their way into California (the owner gleefully showed them off to the media at every conceivable opportunity), but Calaveras County officials ruled amid escalating controversy that the animals could indeed complete. Perhaps it was a foregone conclusion, but all this publicity brought in record crowds to the celebrated doings. Everybody wanted to see the fierce frogs in action. After all, how far could such a powerful creature leap? Rumor had it that the frogs regularly hopped across wide streams in their native land. Well, when all was said and done, the results were rather disappointing for the highly touted amphibians. It turned out that the winner was an unassuming small-fry, some youngster's favorite regulation-sized frog. The African carnivores barely got off the launching pad. It was conjectured by the more conspiracy-minded that somebody had fed them too many bull frogs for breakfast. Historic Angels Camp, which yielded vast fortunes in gold from Mother Lode veins during the mid to late 1800s, lies in the western foothills of the Sierra Nevada--the Snowy Range. Much of this Gold Rush country area is underlain by three famous Tertiary Period geologic rock formations: the middle Eocene Ione Formation (roughly 48 to 45 million years old), the late Oligocene to early Miocene Valley Springs Formation (dated by radiometric means at about 29 to 20 million years old in the Sierra foothills Mother Lode district) and the late middle Miocene to late Pliocene Mehrten Formation, dated through radiometric methodology at 11.6 to 2.59 million years old. The older Ione Formation accumulated in floodplains, estuaries, lagoons, deltas, mashes-swamps, and shallow marine waters (based on extraordinarily rare occurrences of unquestioned marine mollusks) along the eastern shores of a vast inland sea during regionally sub-tropical middle Eocene times--a sea that had flooded, transgressed, what is now California's Great Central Valley during the earlier portions of the Eocene, approximately 53 million years ago. In the vicinity of Ione (38 miles north of Angels Camp), that Ione sea left behind world-renowned commercial deposits of extraordinarily pure silica sand and high-grade kaolinite clays--in addition to extensive accumulations of the rare and valuable Montan Wax-rich lignite, which is mined commercially at only two places in the world--the other Montan Wax site is in Germany; lignite of course is classified as a type of low-grade coal whose alteration of original vegetation has proceeded further than in peat, but obviously not as great as anthracite coal. Montan Wax occurs quite rarely in the geologic record when the waxy substance which once protected the original plant leaves from extremes of climate did not deteriorate, but instead enriched the coal. Commercial applications for Montan Wax include polish, carbon paper, road construction, building, rubber, lubricating greases, fruit coating, water proofing and leather finishing. All of these mineral commodities--silica sands, kaolinite clays and Montan Wax-yielding liginites--have been mined in the Ione area by open-pit methods for many decades. As a matter of fact, today the Ione lignites remain California's only actively mined coal resources. Not far from the community of Ione, on private property, lies an especially rich fossil leaf-bearing section of the middle Eocene Ione Formation that paleobotany aficionados affectionately call "Lygodium Gulch"--a site informally named in honor of the common well preserved specimens of a climbing fern encountered there--Lygodium kaulfussi (probably best known from its spectacularly abundant occurrences in the late early Eocene Green River Formation and the lower middle Eocene Bridger Formation of Utah, Wyoming, and Colorado), which most closely resembles the living American climbing fern Lygodium palmatum, now endemic to the US southeastern states (roughly the Appalachian territories down through the South). It is an as-yet completely undescribed fossil flora, characterized by an absence of leaves with serrated edges; all Ione Flora botanic specimens encountered possess entire margins; that is to say, the leaf edges are uniformly smooth, lacking notches. Such a prevalence of smooth-margin fossil leaves is in botanical analyses traditionally indicative of unusually wet and warm paleoenvironments--decidedly subtropical, in the main. Even though abundant leaf material from Lygodium Gulch and several additional productive Ione Formation localities in the vicinity of Ione is presently stored in the archival paleobotany catacombs of the University California Museum of Paleontology in Berkeley--the cumulative culmination of multiple collecting expeditions by various folks over a period of 12 years (1991 to 2003)--to the best of my knowledge (as of 2018) no formal peer-reviewed scientific examination of the middle Eocene Ione Flora exists. Directly above the Eocene Ione Formation, in nonconformable stratigraphic relations (denoting a lengthy hiatus in regional terrestrial deposition), lies the late Oligocene to early Miocene Valley Springs Formation--a mid Cenozoic Era interval characterized by rhyolitic pyroclastic flows and airfall ash layers that accumulated within an ancestral Sierra Nevada foothill district punctuated by ephemeral lakes and localized vegetation-lush watercourses. While productive paleobotanical evidence is only sporadically encountered in the Valley Springs Formation, one specific locality on private property near San Andreas (12 miles northwest of Angels Camp), the County Seat of Calaveras County, does indeed yield numerous undescribed (in the professional paleobotanical literature) early Miocene leaves of oaks, willows, and an extinct fig, all accurately dated by radiometric methods at 22.9 million years old. The specimens occur as excellently preserved impressions set within a whitish-weathering rhyolite tuff that gold seekers of the early 1900s expelled from a now abandoned drift mine excavation. Supplemental Valley Springs Formation fossil leaves from a few additional sites in California's Gold Country, western foothills of the Sierra Nevada--mainly in the vicinity of State Route 49 between Ione and Angels Camp--provide tantalizing paleoenvironmental indications of an early Miocene scene approximately 23 million years ago. The Valley Springs Flora is not large, yet it sheds invaluable light on an important period in mid Tertiary geologic history. Plants secured from all Valley Springs Formation localities include: undescribed pine; Nutmeg yew; Chinese maple; Boxelder maple; Oregon grape; an extinct alder; Pasadena oak; Canyon live oak; Chinese evergreen oak; swampbay; California bay; an extinct fig similar to the extant Moreton Bay fig; Western sycamore; Monterey ceanothus; Catalina ironwood (now grows in the wild only on the Channel Islands off the coast of southern California); Serpentine willow; and Western soapberry. The geologically younger late Miocene to late Pliocene Mehrten Formation developed as andesitic sedimentary detritus within flood plains of rivers that had their source in the nascent Sierra Nevada to the immediate east. Some portions of the Mehrten contain thick beds of auriferous gravels, similar in richness to the older (Eocene-age) and more famous accumulations farther northeast in the western foothills of the Sierra Nevada. Many Gold Rush-era drift mines and shafts penetrate these gold-bearing gravels throughout the Mother Lode belt, and more recent explorations have demonstrated conclusively that productive horizons can still be discovered. Abundant fossil plants have also been collected from at least two places in the late Miocene portions of the Mehrten Formation. One specific site near Columbia State Park, 26 miles south of Angels Camp--the fossil-bearing bed lies on private property, so I am not at liberty to divulge its exact location--has yielded abundant fossil leaves, a botanic association that provides vital information about the paleoenvironment of the California Gold Country approximately 10 million years ago. Side bar: during my first visit to the locality, I contracted a devastating case of poison oak dermatitis, which ultimately prompted a late night trip to an emergency room to acquire a physician's prescribed two-week regimen of steroids--the proscribed medical treatment for such an extreme reaction to urushiol. Some 28 species of Miocene plants have been identified from the Columbia site, including Chinese maple, laurel sumac, American holly, Mexican grapeholly, Oregon grape, Pagoda dogwood, Black tupelo, Pacific madrone, Chinese rhododedron, extinct Asiatic oak (first specimen discovered at the Pliocene-age Petrified Forest in Sonoma County, California), Engelmann oak, coastal sage scrub oak, Bitternut hickory, swampbay, California bay, Eastern redbud, New Mexico locust, Southern magnolia, Desert olive, Western sycamore, Alabama supplejack, Mountain mahogany, Chinese hawthorn, Brewer's willow, Lewis' mock-orange, western hackberry, American elm, and Knobcone pine. The specimens suggest that a mixture of four distinct floral communities existed here 10 million yeas ago: A border-redwood element, with modern relatives now living in the central Sierra Nevada, south Coast Ranges, and southern California; an oak woodland-chaparral association, presently distributed throughout the Southwest; an eastern American element, whose modern-day representatives now live in the southeastern United States (elm and magnolia, in particular); and an East Asian element, with now living species native to China and the Philippines. Based on the known needs of living members of the fossil flora, precipitation patterns were quite different some 10 million years ago in the ancestral Gold Country. Rainfall was roughly 25 to 30 inches per year, distributed throughout the winter and summer months. Today summers are characteristically dry; a continental, Mediterranean climate has eliminated from the modern flora all members of the East Asian and eastern American botanic communities. It is estimated that the fossils near Columbia accumulated at an elevation no higher than 500 feet. Presently, the locality lies at an altitude of 2,000 feet. Topographic relief in the region was apparently rather low. The late Miocene Sierra foothill belt was essentially a broad flood plain with interspersed undulating hills in which rivers and streams wandered their way to the Pacific Ocean to the west. According to climatic preferences of modern-day relatives of the fossil plants, both summer and winter months were considerably more moderate some 10 million years ago. Winter weather was probably quite comfortable since frosts were rare if not nonexistent in the lowlands. And while summer temperatures likely exceeded 90 degrees at times, there is no indication that they often topped 100. The moderating influence of sea breezes from the nearby Pacific, which had periodically flooded the Great Central Valley through the Tertiary Period, probably contributed to an almost perfect climate. Today, summertime temperatures in the Sierra foothills regularly surpass 100 degrees, and pollution from the Great Central Valley to the west surges against the base of the mountains with increasing frequency. A second exceptional Mehrten Formation paleobotanical locality occurs several miles east of Nevada City/Grass Valley (about 85 miles north of Angels Camp). It's absolute geologic age is established through radiometric analyses at 9.5 million years old, or late Miocene on the geologic time scale. Although the leaf-rich andesitic shales of fluviatile origin had been exposed by hydraulic gold miners during the mid 1850s to 1870s (a gold nugget taken from the diggings in 1855 weighed in at 11.6 pounds--the 22nd-heaviest gold nugget ever discovered in California), nobody bothered to study the remarkable paleobotany preserved there until the early 1940s. 32 species of late Miocene plants have been identified from the Mehrten locality east of Nevada City/Grass Valley (they are contiguous communities in California's northern Mother Lode country), including: Port orford cedar (not really a cedar, of course, but rather a cypress); Coast redwood; Boxelder maple; an extinct species of Mahonia (barberry); oval-leaved viburnum; Pacific madrone; manzanita; Sierra laurel; Blue oak; Valley oak; California black oak; Oracle oak; an extinct oak similar to the extant Chinese evergreen oak; Oriental white oak; Interior live oak; American sweetgum; Ohio buckeye; Eastern black walnut; Red bay; California bay; roundleaf greenbrier; Western sycamore; Alabama supplejack; Buckbrush; mountain hawthorn; Hollyleaf cherry; Black cottonwood; Quaking aspen; Fremont cottonwood; Shining willow; Mexican buckeye; American elm; an extinct species of grapevine. Today, the Mehrten Flora east of Nevada City/Grass Valley resides at an altitude slightly over 4,000 feet within a mixed-conifer Sierran forest association of Ponderosa pine, Incense cedar, White fir, and California Black oak. But some 9.5 million years ago, the fossil flora likely accumulated at elevations no higher than 2,000. The paleoenvironmental setting probably resembled areas in California that host the southernmost occurrences of Coast Redwood--notably Big Sur and the south side of Carmel Valley (northwest of Big Sur), approximately 7.5 miles inland from the Pacific Ocean. Precipitation was in the neighborhood of 35 to 40 inches per year, and that distributed liberally during both the summer and winter months--a weather pattern that contrasts radically with modern Mediterranean-style meteorology, where all effective rain falls during the winter months. Temperatures were much more moderate than those at the fossil site today, with cooler summers and little to no frost during the colder months (even at 4,000 feet, Sierran summer readings surpass 90 degrees). In addition to the rich paleobotanical record, including as-yet undescribed petrified woods, the Mehrten Formation also yields locally plentiful vertebrate fossil material approximately 7 to to 4 million years old, primarily from private properties in the vicinity of Turlock Lake and Camanche Reservoir (Greg Francek, a most paleo-perspicacious ranger with the East Bay Municipal Utility District discovered the Camanche Lake-area fossil vertebrates in 2020), western foothill territories of the Sierra Nevada. The fossil list includes: ground sloths (Megalonyx mathisi, Pliometanastes protistus); dogs (Borophagus parvus, Osteoborus, Vulpes sp.); cats (Felis sp., Machairodus coloradensis, Pseudaelurus sp.); a badger (Pliotaxidea garberi); racoon (Procyon sp.); beavers (Castor sp. and Dipoides williamsi); a vole (Copemys sp.); pocket gopher Cupidinimus sp.); Kangaroo rat (Dipodomys sp.); North american rock squirrel (Otospermophilus argonotus); hares (Hypolagus sp.); horses (Dinohippus coalingensis, Hipparion mohavense, Nannippus tehonensis, Neohipparion molle, Pliohippus coalingensis, P. interpolatus); rhinos (Aphelops sp., Teleoceras sp.); gompotheres (Gomphotherium sp., Platybelodon sp.); mastodons (Mammut americanum); camels (Altomeryx sp., Paracamelus sp., Pliauchenia edensis, Procamelus sp.); peccary (Prosthennops sp.); pronghorns (Garberoceras sp., Merycodus sp., Sphenophalos sp., Tetrameryx sp.); deer (Pediomeryx sp.); a tapir not yet described in the scientific literature; Pacific newt (Taricha); Pacific giant salamander (Dicamptodon); Slender salamanders (Butrachoseps); Climbing salamanders (Aneides); an extinct giant tortoise (Hesperotestudo); Spotted turtle (Clemmys); Gopher tortoises (Gopherus); Star tortoises (Geochelone); an extinct giant spike-toothed salmon Oncorhynchus rastrosus); and Sacramento blackfish (Orthodon). Most of the Mehrten mineralized skeletal material derives from several classic and long-established quarries, but one newer discovery described in a 2018 scientific document yielded something rather extra-extraordinary, as it were--canid coprolites--AKA, petrified poop from Borophagus parvus, an extinct bone cracking dog, probably analogous in behavior to the modern striped and brown hyenas. The Mehrten Formation fossil feces, collected some 55 miles south of Angels Camp in a transition zone situated between the Great Central Valley and the western foothills of the Sierra Nevada, provided the first unambiguous evidence that Borophagus canids (obligate large-prey hunters) consumed large amounts of bone, an idea that vertebrate paleontologists had long suspected but could never directly prove until now. In addition to the "Big Three" Tertiary Period leaf-bearing geologic rock units exposed in California's Gold Rush district (Ione Formation, Valley Springs Formation, and Mehrten Formation), a second major fossil plant-bearing area can be explored in the vicinity of Carson Pass, Sierra Nevada proper, at elevations from 8,000 to 9,200 feet; the turnoff is at Jackson, the County Seat of Amador County, about 11 miles east of Ione (28 miles north of Angels Camp). Not far from the famed summit, for example, named after intrepid Mountain Man and Army scout Kit Carson, locally abundant petrified woods--including at least one stump--occur within an unnamed middle Miocene formation, dated by radiometric methods (radioactive isotope analyses) at 14.7 million years old--a rock unit technically categorized as a volcanic debris flow/braided stream deposit, with common inclusion clasts that might represent repeated avalanches. Fossil leaves can also be found near Carson Pass--from a specific site the late paleobotanist Daniel I. Axelrod (July 16, 1910 – June 2, 1998) had under formal scientific investigations for at least four decades; as a matter of fact--family, friends, and colleagues of Dr. Axelrod scattered his ashes in the vicinity of Frog Lake, not far from Carson Pass, on what would been his 88th birthday, July 16, 1998. The fossils occur at an elevation of approximately 9,200 feet in the andesitic sandstones and shales of an unnamed middle Miocene geologic rock unit calculated at around 16 million years old (preliminary geologic evaluations had placed the fossil flora in the Relief Peak Formation); the paleobanically significant sedimentary matrix represents stream and hyperconcentrated flood deposits, yielding a chiefly riparian association of plants whose modern day counterparts, in general, live at elevations no higher than 2,500 feet. Taxa dominants include the leaves of maple (Acer), tupelo (Nyssa), sycamore (Platanus), avocado (Persea), poplar (Populus), lingnut (Pterocarya), Catalina Ironwood (Lyonothamnus--a tree that presently grows in the wild only on the Channel Islands off the coast of southern California), oak (Quercus), elm (Ulmus), and willow (Salix); interestingly, no conifers occur in the so-called Carson Pass Flora. Today, the fossil site lies in the arctic-alpine zone of fell-fields and meadowland, above a subalpine forest of whitebark pine and mountain hemlock. After reflecting on the rich regional Cenozoic Era paleontology of California's Carson Pass/Gold Rush areas--and visiting Angels Camp--it's time for the ride to the High Sierra fossil plants. To reach the Mount Reba fossil-bearing area, first take State Route 4 northeast out of Angels Camp toward Ebbetts Pass. At a point 23 miles from Angles Camp, you will arrive at the turnoff to Calaveras Big Trees State Park. I most definitely recommend a side visit. Here you will find two of the finest groves of giant sequoia in existence. The North Grove receives most of the visitor attention, but if you really wish to experience the overwhelming wonder of an essentially pristine giant sequoia floral community, then head over to the less-frequented South Grove a few miles from the entrance gate. A two-mile hike is required to reach the South Grove, but the going is easy (no serious elevations to ascend) and, once amidst the big trees, you will likely marvel at the undisturbed nature of the spectacle. The associated understory of plants which contribute to an ancient giant sequoia forest have not been trampled into submission as, unfortunately, they have been in Sequoia National Park, where millions of visitors each year wander among the trees, preventing the natural vegetation from reestablishing itself. This South Grove shows off the same unique grouping of big trees, pines, shrubs, and deciduous trees--all unchanged--that once covered all of west-central Nevada and most of east-to-central California some 16 to 5 million years ago. Once you've explored Calaveras Big Trees State Park, it's time to proceed onward to the turnoff to the Mount Reba fossil plant locality in the general vicinity of an ultra-popular ski resort. From late fall to early spring thousands of enthusiasts pack up their equipment and head this way--the quality of the snow pack is according to experts quite extraordinary, conducive to a sensational skiing experience. But prior to the ascent to the fossiliferous locality--assuming that the United States Forest Service (USFS) continues to allow vehicular access, mind you--take a moment to dispassionately evaluate your own ability to negotiate off-road a four-wheel drive vehicle over a steep, rocky, unimproved path in the mountains. I am not trying to scare anybody off here--far from it. In a seance, I am appealing to a sense of adventure. At the same time, I am providing a gentle warning to novice off-road drivers that, while the route is far from expert-only, it does require a modicum of technical proficiency in two or three places. Most of the trail is easily and safely negotiated. If authorities no longer permit motorized access, you'll just have to hike the remaining distance to the Disaster Peak Formation paleobotanical area--the very same way I did upon my first visit; even though officials allowed vehicular travel at that date, I nevertheless voluntarily chose to walk to the site, not confidently anticipating that first time around that I'd be able to safely negotiate the unknown incline in my four-wheel drive mechanism. Once at the convenient parking area near the fossil-bearing site at an elevation of almost 9,000 feet--and contingent of course on permission from the USFS to continue to collect fossil plants here, walk downslope from the parking spot along the narrow dirt trail. The first outcrops you encounter, in the roadcut along the left side of the path, contain the 7 million-year-old leaves. The fossil plants occur in the yellow-to-buff, moderately compacted andesitic sandstones of the upper Miocene Disaster Peak Formation. Widely scattered pieces of unidentified petrified wood also occur along the steep slopes to the right of the trail. But watch your footing here, as trying to hike over the weathered sandy mudstones and volcanic rocks is hazardous. The Disaster Peak Formation exposed along the trail is approximately 29 feet thick. It's primarily a mudstone-sandstone andesite breccia--the hardened material remaining from a mudflow that moved with inexorable inevitability down a moist hillslope some 7 million years ago, a massive mudflow event probably triggered by a volcanic eruption in the neighborhood. Two rather thin sandstone beds in the section--2 feet, and 1.5 feet thick, respectively--yield all of the moderately common fossil leaves; the remainder of the deposit is unfossiliferous. A distinctive feature of the fossils in the sandstone is that they are curled and twisted, a telltale style of preservation that indicates that the mudflow contorted the leafy structures as it slid downslope. Altogether, 14 species of fossil plants have been secured from the Disaster Peak Formation. The four most abundant forms in the sandstones are leafy branchlets from a cypress, Cupressus mokelumnensis (an extinct cypress that is similar to the living Chinese weeping cypress--now native to China); leafy twigs from a Douglas-fir, Pseudotsuga sonomensis; entire leaves from an evergreen live oak, Quercus pollardiana (Canyon live oak); and leaves from a species of tanbark oak, Lithocarpus klamathensis. In decreasing order of relative prevalence, the flora also contains a cattail, Typha lesquereuxii; a willow, Salix wildcatensis (arroyo willow); a white fir, Abies concoloroidea; a giant sequoia, Sequoiadendron cheneyii; a second species of willow, Salix hesperia (Pacific willow); an elm, Ulmus affinis (an extinct species most similar to the extant American elm); a species of sugar pine, Pinus prelambertiana; a pine, Pinus sturgisii (western yellow pine); a juniper, Juniperus sp.; and a third species of willow, Salix boisiensis (Scouler's willow). In general, the fossil floral association resembles a modern-day Douglas-fir forest in the western foothills of the central to northern Sierra Nevada, at elevations of 2,000 to 3,000 feet; today, the fossiliferous section rests at an altitude of 8,650 feet, above the local timberline in the upper subalpine belt. During the upper Miocene, rainfall was likely as high as 40 inches per year, with storms distributed in both winter and summer months. This is in dramatic contrast with present-day weather patterns, which release virtually all of the effective precipitation as snow during the winter. But 7 million years ago summertime rain was a necessary occurrence, in order to account for the presence of cypress and elm in the local fossil record. The species of cypress, Douglas-fir, evergreen live oak, and tanbark oak--which comprise 97.8 percent of the fossil specimens recovered from the flora--clearly lived nearest the actual site of deposition, probably along the cool shady north-facing slopes of a southwesterly draining valley. Farther upstream, white fir, sugar pine, yellow pine, and giant sequoia contributed to a mixed conifer forest. The drier slopes in this area supported specimens of juniper. The three species of willow thrived along the watercourses, no doubt forming dense thickets. The lone species of elm in the fossil record could have lived in the mixed conifer forest, where greater rates of precipitation would favor its survival. An interesting observation is that the most abundant member of the Disaster Peak Formation flora, the specific species of cypress, no longer lives anywhere in the United States; its closest modern-day relative is now native to China. After analyzing the fossil leaf, twig, and branchlet material secured from the upper Miocene Disaster Peak Formation, paleobotanists have arrived at a fascinating line of thought. Perhaps it is possible to determine the time of year when the mudflow engulfed the plants. Numerous specimens of cypress, Douglas-fir, and oak, for example, appear to represent immature leafy structures---signifying that before they became buried by the mudflow the plants had just begun their first spurts of growth during the new season. It is a tentative conclusion, but the overall size and shape of the preserved plant structures suggests that the event which preserved them occurred during either spring or early summer. Here is a fossil plant locality worth visiting: But only during the "dead of summer" through early fall, of course, when the roads at higher Sierra elevations remain "reliably" passable. Not only are excellent leaf and twig specimens from 14 species of upper Miocene plants available, but the scenery up there is absolutely stunning--a wide vista that takes in mile after mile of the pristine High Sierra Nevada back country, a true wilderness, one of the great natural treasures in America. As you stand there at an elevation of 8,650 feet, above local timberline, the Disaster Peak Formation fossils prove that 7 million years ago Douglas-fir, cypress, and giant sequoia thrived where today no trees exist. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictues. Left--A paleobotany aficionado inspects an outcrop of the fossil plant-bearing upper Miocene Disaster Peak Formation. The primary fossil leaf locality in the Disaster Peak Formation occurs just downslope from this spot. The vista is almost due north. Sierra Nevada batholithic grantites in panoramic perspective to the skyline. That brownish peak at upper left is composed of Miocene-age andesitic volcanic rocks. Right--Enthusiastic paleobotany participants investigate the primary fossil plant locality in the upper Miocene Disaster Peak Formation. Viewing perspective is roughly northward. Today, the site lies at an altitude of 8,640 feet, but the 14 species of plants preserved here prove that 7 million years ago the very spot, now slightly above the local timberline, would have resembled a modern Douglas-fir forest in the lower western foothills of the Sierra Nevada at elevations no higher than 2,500 feet, with subordinate groves of giant sequoia thriving nearby. The four most abundant fossil plant forms secured from the Disaster Peak Formation sandstones are leafy branchlets from a cypress, Cupressus mokelumnensis (an extinct cypress that is similar to the living Chinese weeping cypress--now native to China; leafy twigs from a Douglas-fir, Pseudotsuga sonomensis; entire leaves from an evergreen live oak, Quercus pollardiana (Canyon live oak); and leaves from a species of tanbark oak, Lithocarpus klamathensis. In decreasing order of relative prevalence, the flora also contains a cattail, Typha lesquereuxii; a willow, Salix wildcatensis (arroyo willow); a white fir, Abies concoloroidea; a giant sequoia, Sequoiadendron cheneyii; a second species of willow, Salix hesperia (Pacific willow); an elm, Ulmus affinis (an extinct species most similar to the extant American elm); a species of sugar pine, Pinus prelambertiana; a pine, Pinus sturgisii (western yellow pine); a juniper, Juniperus sp.; and a third species of willow, Salix boisiensis (Scouler's willow). |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--A seeker of paleobotanical adventure inspects andesitic tuffs of the upper Miocene Disaster Peak Formation for fossil plant material. Relatively common pieces of as-yet unidentified petrified wood weather out of this specific volcanic sequence in the Disaster Peak Formation. Right--Directional orientation here is roughly due north from the upper Miocene Disaster Peak Formation fossil locality. Sierra Nevada granitic basement complex spreads to the horizon. Peak at upper left is developed in late Miocene andesite volcanics. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

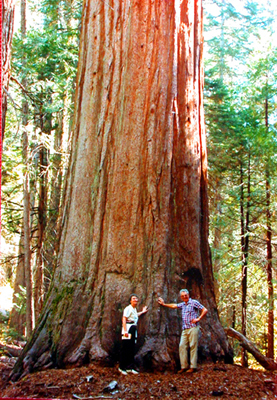

Click on the images for larger pictures. Seekers of outdoor adventure stand at the base of a Big Tree, a giant sequoia (Sierra redwood), at the South Grove, Calaveras Big Trees State Park, Calaveras County, California, western slopes of the Sierra Nevada. Another Big Tree rises at far right; that's the trunk of a sugar pine--an impressive conifer in its own right--at foreground left, by the way. The South Grove at Calaveras Big Trees makes an excellent side trip when visiting the High Sierra Nevada fossil plants in the upper Miocene Disaster Peak Formation. Middle--Botany enthusiasts explore the South Grove of giant sequoias (Sierra redwood) at Calaveras Big Trees State Park, Calaveras County, California, western slopes of the Sierra Nevada. The South Grove at Calaveras Big Trees makes an excellent side trip when visiting the High Sierra Nevada fossil plants in the upper Miocene Disaster Peak Formation. By the way, many of those other conifers in the photograph are amazingly impressive specimens in their own right. Right--Botany enthusiasts explore the South Grove of giant sequoias (Sierra redwood) at Calaveras Big Trees State Park, Calaveras County, California, western slopes of the Sierra Nevada. The South Grove at Calaveras Big Trees makes an excellent side trip when visiting the High Sierra Nevada fossil plants in the upper Miocene Disaster Peak Formation. By the way, many of those other conifers in the photographs are amazingly impressive specimens in their own right. |

|

|

|

|

Click on the image for larger picture. The Mark Twain cabin, California Historical Landmark 138. A replica (constructed in 1922--though the fireplace and chimney are original) of the cabin on Jackass Hill, about 6 miles south of Angels Camp in California's Gold Rush Country, where Mark Twain (given name Samuel Langhorne Clemens) lived with the Gillis brothers (local miners) during the winter of 1864-'65. He arrived there on December 4, 1864, from San Francisco. It's the place where in early 1865 he wrote "The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County" (eventually published in the New York Saturday Press on November 18, 1865)--the very short story that first brought him national fame as a writer. A Google Earth street car perspective that I edited and processed through photoshop. Here's the note Twain made in his notebook in January, 1865, while staying at Jackass Hill--the germ of the story that eventually became "The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County:" "Coleman with his jumping frog — bet stranger $50 — stranger had no frog & C got him one — in the meantime stranger filled C's frog full of shot & he couldn't jump — the stranger's frog won." |

|

|

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left and right--Students and their professors from a university and a community college help the late paleobotanist Howard Schorn (next bottom photo, below) standing in trench in pale blue long-sleeve shirt and wearing a hat)--former Collections Manager of fossil plants at the University California Museum of Paleontology--collect fossil leaves during a two day expedition to classic Lygodium Gulch, not far from Ione, California, on private property, in the middle Eocene Ione Formation, approximately 49 to 45 million years old. The Ione is one of three fossil plant-bearing Tertiary Period rock formations one can examine in California's Gold Country, western foothills of the Sierra Nevada, along the route to the upper Miocene Disaster Peak Formation paleobotanical locality in the High Sierra Nevada, Alpine County; the other two are the late Oligocene to lower Miocene Valley Springs Formation and the upper Miocene Mehrten Formation. Two supplemental areas in the California's High Sierra Carson Pass region--east of Jackson (county seat of Amador County)--also yield Tertiary-age petrified wood and fossil leaves from two unnamed (in the published scientific literature) geologic rock formations of middle Miocene age. In addition to abundant, as-yet unidentified leaves (as of 2018, no scientific analysis of the Ione Flora has ever been published in the peer-reviewed paleobotanical literature), Lygodium Gulch also yields important specimens of the species for which the locality was informally named--an extinct climbing fern, Lygodium kaulfussi, whose closest living analog is the American climbing fern, Lygodium palmatum, now endemic to the US southeast, from roughly Appalachia to the South. Image taken on October 27, 2002. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--A roadcut in the Carson Pass area that exposes an unnamed middle Miocene unit, dated by radiometric methods (radioactive isotope analyses) at 14.7 million years old; locally in the Carson Pass district this specific rock formation produces abundant petrified woods. It's primarily a combination volcanic debris flow/braided stream deposit, with common inclusion clasts that might represent repeated avalanches. A Google Earth street car perspective that I edited and processed through photoshop. Middle--A view southward near Carson Pass to a Sierra Nevada spectacle--and, a famous fossil leaf locality--a site the late paleobotanist Daniel I. Axelrod (July 16, 1910--June 2, 1998) had under formal scientific investigations for at least four decades. That patch of shale and sandstone at lower right yields common fossil leaves from an unnamed middle Miocene geologic rock unit usually calculated at around 16 million years old (originally thought to represent the Miocene Relief Peak Formation); the paleobanically significant sedimentary detritus accumulated in streams and as hyperconcentrated flood deposits. Elevation here is around 9,200 feet, above the local timberline. Note patches of lingering snow; photograph taken during a late August visit. The middle Miocene leaf locality near Carson Pass yields a chiefly riparian association whose modern day counterparts in general live at elevations no higher than 2,500 feet. Taxa dominants include the leaves of maple (Acer), tupelo (Nyssa), sycamore (Platanus), avocado (Persea), poplar (Populus), lingnut (Pterocarya), Catalina Ironwood (Lyonothamnus--a tree that presently grows in the wild only on the Channel Islands off the coast of southern California), oak (Quercus), elm (Ulmus), and willow (Salix); interestingly, no conifers occur in the so-called Carson Pass Flora. Today, the fossil site lies in the arctic-alpine zone of fell-fields and meadowland, above a subalpine forest of whitebark pine and mountain hemlock. Right--Frog Lake (elevation 8,865 feet) in the vicinity of Carson Pass. Near here--on July 16, 1998--a group of family and friends spread the ashes of paleobotanist Daniel I. Axelrod on the anniverary of what would have been his 88th birthday. |

|

|

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left and right: Two views of a prime fossil leaf locality, presently situated on private property, in the lower Miocene portion of the late Oligocene to lower Miocene Valley Spring Formation. The whitish areas in both photographs represent leaf-bearing blocks of rhyolite tuff (dated radiometrically at 23 million years old) that gold miners ejected from a now abandoned drift mine. Rather common undescribed (in the professional paleobotanical literature) leaf impressions of oaks, willows, and an extinct variety of fig can be found here on those dumps of Valley Springs Formation rhyolite tuff--with the property owner's explicit permission, of course. Supplemental Valley Springs Formation fossil leaves from additional sites in California's Gold Country, western foothills of the Sierra Nevada--from rhyolitic exposures situated between Nevada City/Grass Valley to the north and Le Grange to the south--provide tantalizing paleoenvironmental indications of an early Miocene scene approximately 23 million years ago. The Valley Springs Flora is not large, yet it sheds invaluable light on an important period in mid Tertiary geologic history. Plants secured from all Valley Springs Formation localities include: undescribed pine; Nutmeg yew; Chinese maple; Boxelder maple; Oregon grape; an extinct alder; Pasadena oak; Canyon live oak; Chinese evergreen oak; swampbay; California bay; an extinct fig similar to the extant Moreton Bay fig; Western sycamore; Monterey ceanothus; Catalina ironwood (now grows in the wild only on the Channel Islands off the coast of southern California); Serpentine willow; and Western soapberry. The Valley Springs Formation is one of three fossil plant-bearing Tertiary Period rock formations one can examine in California's Gold Country, western foothills of the Sierra Nevada, along the route to the upper Miocene Disaster Peak Formation paleobotanical locality in the High Sierra Nevada, Alpine County; the other two are the middle Eocene Ione Formation and the upper Miocene Mehrten Formation. Two supplemental areas in the California's High Sierra Carson Pass region--east of Jackon (county seat of Amador County)--also yield Tertiary-age petrified wood and fossil leaves from two unnamed (in the published scientific literature) geologic rock formations of middle Miocene age. |

|

|

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--The late-middle Mehrten Formation fossil leaf-bearing site (about 10 million years old) near Columbia State Park, California, about 26 miles south of Angels Camp (convenient turnoff point for the Disaster Peak Formation paleobotanical site)--an old gold prospect currently on private property, marked by the prominent excavation. Some 28 species of Miocene plants have been identified from this locality, including Chinese maple, laurel sumac, American holly, Mexican grapeholly, Oregon grape, Pagoda dogwood, Black tupelo, Pacific madrone, Chinese rhododedron, extinct Asiatic oak (first specimen discovered at the Pliocene-age Petrified Forest in Sonoma County, California), Engelmann oak, coastal sage scrub oak, Bitternut hickory, swampbay, California bay, Eastern redbud, New Mexico locust, Southern magnolia, Desert olive, Western sycamore, Alabama supplejack, Mountain mahogany, Chinese hawthorn, Brewer's willow, Lewis' mock-orange, western hackberry, American elm, and Knobcone pine. An archival photograph of a classic fossil leaf localitiy--one of three famous Tertiary Period fossil plant-bearing rock formations one can examine in California's Gold Country, western foothills of the Sierra Nevada, along the route to the Disaster Peak Formation plants in the High Sierra Nevada, Alpine County; the other two are the middle Eocene Ione Formation and the late Oligocene to lower Miocene Valley Springs Formation. Photograph taken during the early 1940s; courtesy a specific scientific publication. Two supplemental areas in the California's High Sierra Carson Pass region--east of Jackon (county seat of Amador County)--also yield Tertiary-age petrified wood and fossil leaves from two unnamed (in the published scientific literature) geologic rock formations of middle Miocene age. Right--This is the early-late Mehrten Formation leaf-yielding locality (9.5 million years old) several miles east of Nevada City/Grass Valley (they are contiguous communities), northern Mother Lode country, about 85 miles north of Angels Camp (the turnoff point for the Disaster Peak Formation fossil plant-bearing area). The paleobotanic bonanza occurs along the cliff face, originally exposed by hydraulic gold miners in the mid 1850s. A gold nugget from this area, by the way, weighed in at 11.6 pounds, making it the 22nd heaviest gold nugget ever discovered in California. 32 species of late Miocene plants have been identified from this Mehrten locality east of Nevada City/Grass Valley, including: Port orford cedar (not really a cedar, of course, but rather a cypress); Coast redwood; Boxelder maple; an extinct species of Mahonia (barberry); oval-leaved viburnum; Pacific madrone; manzanita; Sierra laurel; Blue oak; Valley oak; California black oak; Oracle oak; an extinct oak similar to the extant Chinese evergreen oak; Oriental white oak; Interior live oak; American sweetgum; Ohio buckeye; Eastern black walnut; Red bay; California bay; roundleaf greenbrier; Western sycamore; Alabama supplejack; Buckbrush; mountain hawthorn; Hollyleaf cherry; Black cottonwood; Quaking aspen; Fremont cottonwood; Shining willow; Mexican buckeye; American elm; an extinct species of grapevine. An archival photograph of a classic fossil leaf localitiy--one of three famous Tertiary Period fossil plant-bearing rock formations one can examine in California's Gold Country, western foothills of the Sierra Nevada, along the route to the Disaster Peak Formation plants in the High Sierra Nevada, Alpine County; the other two are the middle Eocene Ione Formation and the late Oligocene to lower Miocene Valley Springs Formation. Photograph taken during the early 1940s; courtesy a specific scientific publication. Two supplemental areas in the California's High Sierra Carson Pass region--east of Jackon (county seat of Amador County)--also yield Tertiary-age petrified wood and fossil leaves from two unnamed (in the published scientific literature) geologic rock formations of middle Miocene age. |

|

|

|

|

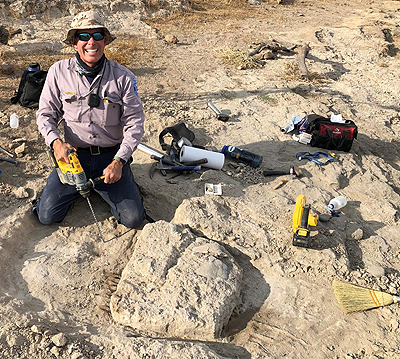

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--Paleobotany enthusiasts (under the auspices of the University California Museum of Paleontology) collect fossil leaves at the Mehrten Formation leaf-yielding locality several miles east of Grass Valley/Nevada City--they are contiguous communities that lie about 85 miles north of Angels Camp (turnoff point for the High Sierra Nevada Disaster Peak Formation fossil plant-bearing area)--northern Mother Lode country. The paleobotanic bonanza occurs along a cliff face, originally exposed by hydraulic gold miners in the mid 1850s. A gold nugget from this area, by the way, weighed in at 11.6 pounds, making it the 22nd heaviest gold nugget ever discovered in California. Photograph taken on October 16, 1993. 32 species of early-late Miocene plants have been identified from this early-late Mehrten Formation locality (9.5 million years old) east of Nevada City/Grass Valley, including: Port orford cedar (not really a cedar, of course, but rather a cypress); Coast redwood; Boxelder maple; an extinct species of Mahonia (barberry); oval-leaved viburnum; Pacific madrone; manzanita; Sierra laurel; Blue oak; Valley oak; California black oak; Oracle oak; an extinct oak similar to the extant Chinese evergreen oak; Oriental white oak; Interior live oak; American sweetgum; Ohio buckeye; Eastern black walnut; Red bay; California bay; roundleaf greenbrier; Western sycamore; Alabama supplejack; Buckbrush; mountain hawthorn; Hollyleaf cherry; Black cottonwood; Quaking aspen; Fremont cottonwood; Shining willow; Mexican buckeye; American elm; an extinct species of grapevine. Middle--EBMUD (East Bay Municipal Utilities District) ranger Greg Francek excavates a shell from the extinct giant tortoise Hesperotestudo at a locality he discovered on EBMUD property near Camanche Reservoir in 2020 (the site is obviously off limits to unauthorized visitors), western foothills of the Sierra Nevada. The ancient reptile resides in the upper Miocene to lower Pliocene Mehrten Formation, approximately 10 to five million years old. In less than a year, technicians had already recovered--in addition to giant tortoise shells and petrified woods--much Cenozoic mammalian skeletal material from proboscidean gomthotheres and mastodons, rhinoceroses, camels, tapirs, and horses. Photograph courtesy East Bay Municipal Utility District. Right--A fossil locality in the upper Miocene to lower Pliocene Mehrten Formation near Turlock Lake, western foothills of the Sierra Nevada, where private paleontology enthusiast Dennis Garber--from roughly 1957 to 1964--collected teeth, skull bones and vertebrae from the extinct giant spike-toothed salmon called scientifically Oncorhynchus rastrosus, a species that in actual life could have grown to eight feet long, weighing an estimated 450 pounds. Mr. Garber's paleontological discoveries came from the level "beach area;" note the paleo-technician standing atop a miniature cliff exposure of the Mehrten Formation in distance. Note that today the fossil sites lie within a state recreational area and are completely off limits to unauthorized collectors. Photograph courtesy Julia Sankey, Jacob Brewer, Janis Basuga, Francisco Palacios, Hugh Wagner, and Dennis Garber. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

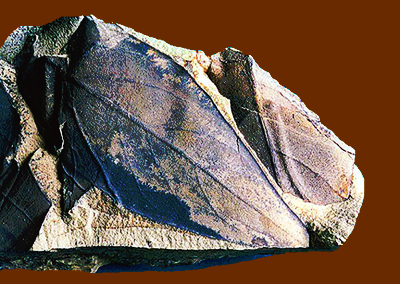

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--Plant specimen preserved on a chunk of andesitic sandstone from the upper Miocene Disaster Peak Formation, High Sierra Nevada, Alpine County, California. Approximately 7 million years old. It's a twig from a Douglas-fir, called scientifically Pseudotsuga menziesii. Middle--An evergreen live oak branchlet, with leaves still attached, from the upper Miocene Disaster Peak Formation, High Sierra Nevada, Alpine County, California. Roughly 7 million years old. Called scientifically Quercus pollardiana--it is the Miocene equivalent of the modern Canyon live oak, endemic to many California mountain ranges. Preserved on a piece of andesitic sandstone. Right--Plant specimen preserved on a chunk of andesitic sandstone from the upper Miocene Disaster Peak Formation, High Sierra Nevada, Alpine County, California. Approximately 7 million years old. It's an evergreen live oak leaf, called scientifically Quercus pollardiana; it most closely resembles the modern Canyon live oak, endemic to many of California's mountain ranges. |

|

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--Fossil plant specimen from the upper Miocene Disaster Peak Formation, High Sierra Nevada, Alpine County, California. Preserved on a chunk of andesitic sandstone. Approximately 7 million years old. It's a branchlet from an extinct variety of cypress, called scientifically Cupressus mokelumnensis; it is most similar to the living Chinese weeping cypress native to southwestern and central China. Photograph courtesy a specific technical document. Middle--Petrified wood from the upper Miocene Disaster Peak Formation, High Sierra Nevada, Alpine County, California. Approximately 7 million years old. Note the US dime currency for scale. Common, but widely scattered pieces of petrified wood occur in the vicinity of the primary leaf-bearing section of the Disaster Peak Formation. Right--Fossil plant specimen from the upper Miocene Disaster Peak Formation, High Sierra Nevada, Alpine County, California. Preserved on a chunk of andesitic sandstone. Approximately 7 million years old. It's a leaf from the willow Salix boisiensis, whose closest living counterpart is Scouler's willow, native to the western United States and ranging through Canada to Alaska. Image courtesy a specific scientific document. |

|

|

|

|

|

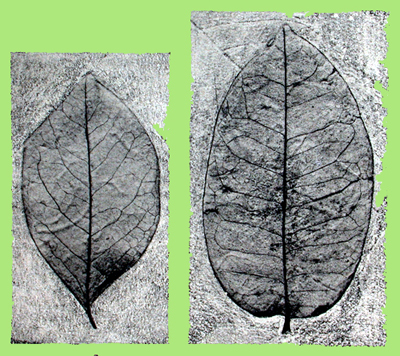

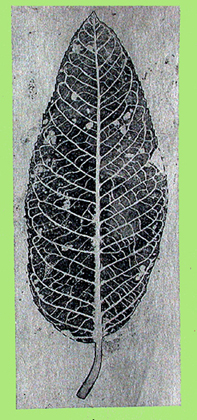

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--A fossil leaf from a Tertiary Period geologic rock formation one can examine in California's Gold Country, western foothills of the Sierra Nevada, along the route to the upper Miocene Disaster Peak Formation plants, High Sierra Nevada. It's an undescribed leaf (as of 2018, not yet identified in the published paleobotanical literature) from the middle Eocene Ione Formation (approximately 48 to 45 million years old) exposed at classic Lygodium Gulch, not far from Ione, Amador County, California. A fossil leaf from a Tertiary Period geologic rock formation one can examine in California's Gold Country, western foothills of the Sierra Nevada, along the route to the upper Miocene Disaster Peak Formation plants, High Sierra Nevada. It's a fig leaf from the lower Miocene Valley Springs Formation, from a locality near San Andreas, County Seat of Calaveras County, Gold Country, California. Called scientifically Ficus macrophyllum--the presumably extinct Miocene counterpart of the living Ficus macrophylla--the Moreton Bay fig native to eastern Australia. Preserved on a chunk of rhyolite tuff. |

|

|

|

|

|

Click on the imagse for larger pictures. Left--A fossil plant from the Carson Pass area, Sierra Nevada, California. It's a petrified stump preserved in an unnamed geologic rock unit dated by radiometric methods (radioactive isotope analyses) at 14.7 million years old; the material from which the stump protrudes is a trachyandesite ash flow tuff, with subordinate debris flow deposits. Photograph courtesy geologists Cathy J. Busby and Keith Putirka. Right--A fossil plant from the Carson Pass area, Sierra Nevada, California. It's a a fossil avocado leaf (genus Persea) from an unnamed geologic rock deposit that paleobotanists usually estimate at around 16 million years old. The specimen came from a locality that presently lies at roughly 9,200 feet, above the local timberline, above a subalpine forest composed of whitebark pine and mountain hemlock. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--A fossil leaf from an Oregon grape, referred to scientifically as Mahonia aguifolium. Specimen is approximately 10 million years old; it's from the early late Miocene Mehrten Formation paleobotanical locality near Columbia State Park. The Mehrten is one of three Tertiary Period geologic rock formations one can examine in California's Gold Country, western foothills of the Sierra Nevada, along the route to the upper Miocene Disaster Peak Formation plants, High Sierra Nevada; the other two are the middle Eocene Ione Formation and the late Oligocene to early Miocene Valley Springs Formation. Two supplemental localities in California's High Sierra Carson Pass area (east of Jackson, county seat of Amador County) also yield petrified woods and fossil leaves from two unnamed (in the published scientific literature) geologic rock formations of middle Miocene age. Middle--Undescribed (in the scientific literature) petrified wood from the upper Miocene to lower Pliocene Mehrten Formation, approximately 10 to five million years old. The specimen came from a locality discovered on private property in 2020 in the vicinity of Camanche Reservoir, western foothills of the Sierra Nevada, California. Photograph courtesy East Bay Municipal Utilities District. Right--A fossil leaf from an oak, named scientifically Quercus remingtoni--it's considered the Miocene analog to the living Quercus morehus, which in actual fact is a naturally occurring hybrid between a deciduous oak (Quercus kelloggii--the California black oak) and an evegreen live oak (Quercus wislizeni--the interior live oak). From the early late Miocene Mehrten Formation fossil leaf locality several miles east of Nevada City/Grass Valley, Northern Mother Lode country, California. It's 9.5 million years old. The Mehrten is one of three Tertiary Period geologic rock formations one can examine in California's Gold Country, western foothills of the Sierra Nevada, along the route to the upper Miocene Disaster Peak Formation plants, High Sierra Nevada; the other two are the middle Eocene Ione Formation and the late Oligocene to early Miocene Valley Springs Formation. Two supplemental localities in California's High Sierra Carson Pass area (east of Jackson, county seat of Amador County) also yield petrified woods and fossil leaves from two unnamed (in the published scientific literature) geologic rock formations of middle Miocene age. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

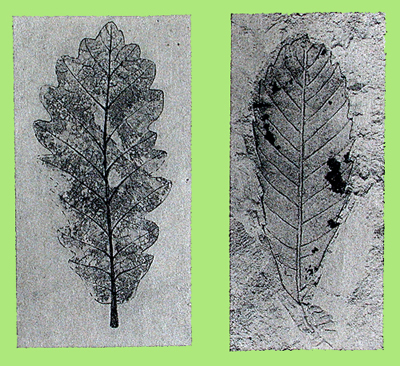

Click on the images for larger pictures. Fossil leaves from the upper Miocene Mehrten Formation locality near Columbia State Park, Gold Country, western foothills of the Sierra Nevada, California. Left--Specimen at left in photograph is from what paleobotanists call Nyssa elaenoides, the Miocene variety of today's Black tupelo; leaf at right in the image is called Rhus mensae, the Miocene counterpart of the modern laurel sumac. Photograph courtesy a specific technical document. Middle--Fossil leaves from the upper Miocene Mehrten Formation locality near Columbia State Park, Gold Country, western foothills of the Sierra Nevada, California. Two oak leaves referred to Quercus convexa, which is the Miocene equivalent of the modern Pasadena oak (also called the Engelmann oak). Photograph courtesy a specific technical document. Right--Fossil leaves from the upper Miocene Mehrten Formation locality near Columbia State Park, Gold Country, western foothills of the Sierra Nevada, California. Left to right: Crataegus newberryi, which most closely resembles the living mountain hawthorn; middle--Philadelphus nevadensis, the Miocene analog of the modern Lewis' mock-orange; Cercocarpus antiquus, which is equivalent to the living mountain mahogany. Photograph courtesy a specific technical document. |

|

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--A fossil leaf from the upper Miocene Mehrten Formation locality near Columbia State Park, Gold Country, western foothills of the Sierra Nevada, California. It's called scientifically Persea coalingensis, the fossil variety of the extant swampbay. Photograph courtesy a specific technical document. Middle--A fossil leaf from the upper Miocene Mehrten Formation locality near Columbia State Park, Gold Country, western foothills of the Sierra Nevada, California. It's called scientifically Carya typhinoides, a Miocene counterpart of the modern Bitternut hickory. Photograph courtesy a specific technical document. Right--A fossil leaf from the upper Miocene Mehrten Formation locality near Columbia State Park, Gold Country, western foothills of the Sierra Nevada, California. It's called scientifically Quercus convexa, the Miocene equivalent of the living Pasadena oak (also called the Engelmann oak). Photograph courtesy a specific technical document. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

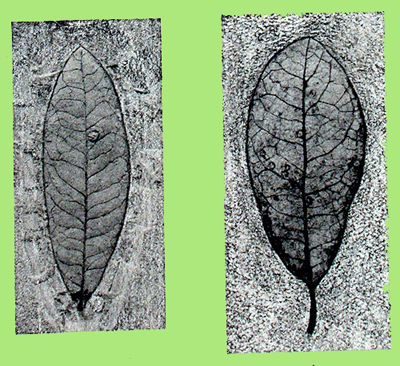

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--A fossil leaf from the upper Miocene Mehrten Formation locality several miles east of Grass Valley/Nevada City (they are contiguous communities), Northern Mother Lode country, California. Called Quercus pseudo-lyrata, the fossil counterpart of the modern California black oak. Photograph courtesy a specific technical document. Middle--A fossil leaf from the upper Miocene Mehrten Formation locality several miles east of Grass Valley/Nevada City (they are contiguous communities), Northern Mother Lode country, California. Called Platanus paucidentata, the Miocene analog to the living western sycamore. Photograph courtesy a specific technical document. Right--Fossil leaves from the upper Miocene Mehrten Formation locality several miles east of Grass Valley/Nevada City (they are contiguous communities), Northern Mother Lode country, California. Two leaves from Quercus remingtoni, a species that paleobotanists consider the Miocene analog to the living Quercus morehus, which is actually a naturally occurring hybrid between a deciduous oak (Quercus kelloggii--the California black oak) and an evegreen live oak (Quercus wislizeni--the interior live oak). Photograph courtesy a specific technical document. |

|

|

|

|

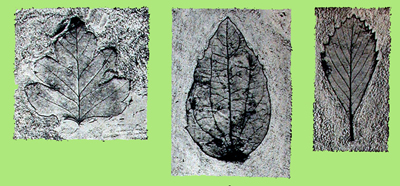

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--Fossil leaves from the upper Miocene Mehrten Formation locality several miles east of Grass Valley/Nevada City (they are contiguous communities), Northern Mother Lode country, California. Leaves from Quercus winstanleyi and Quercus simulata (left to right)--the fossil equivalents of the Oriental white oak and the Chinese evergreen oak, respectively. Photograph courtesy a specific technical document.. Middle--A fossil leaf from the upper Miocene Mehrten Formation locality several miles east of Grass Valley/Nevada City (they are contiguous communities), Northern Mother Lode country, California. Called Populus prefremontii, the Miocene variety of today's Fremont's cottonwood (also called the Alamo cottonwood). Photograph courtesy a specific technical document. Right--A fossil leaf from the upper Miocene Mehrten Formation locality several miles east of Grass Valley/Nevada City (they are contiguous communities), Northern Mother Lode country, California. Called Salix hesperia, the fossil equivalent of the living Pacific willow. Photograph courtesy a specific technical document. |

|

|

|

|

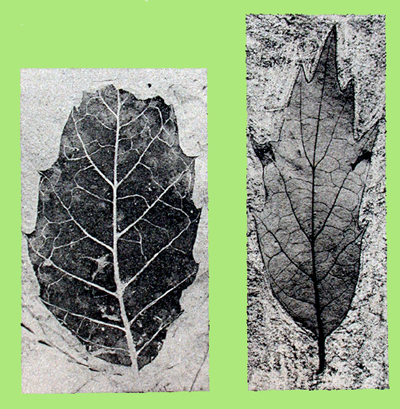

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--A fossil leaf from the upper Miocene Mehrten Formation locality several miles east of Grass Valley/Nevada City (they are contiguous communities), Northern Mother Lode country, California. Called Quercus prelobata, the fossil variety of today's Valley oak. Photograph courtesy a specific technical document. Middle--A fossil leaf from the upper Miocene Mehrten Formation locality several miles east of Grass Valley/Nevada City (they are contiguous communities), Northern Mother Lode country, California. Called Ugnadia clarki, the Miocene counterpart of the extant Mexican buckeye. Photograph courtesy a specific technical document. Right--Fossil leaves from the upper Miocene Mehrten Formation locality several miles east of Grass Valley/Nevada City (they are contiguous communities), Northern Mother Lode country, California. All three leaves belong to Quercus remingtoni, a species that paleobotanists consider the Miocene analog to the living Quercus morehus, which in actual fact is a naturally occurring hybrid between a deciduous oak (Quercus kelloggii--the California black oak) and an evegreen live oak (Quercus wislizeni--the interior live oak). Photograph courtesy a specific technical document. |

|

|

|

|

|

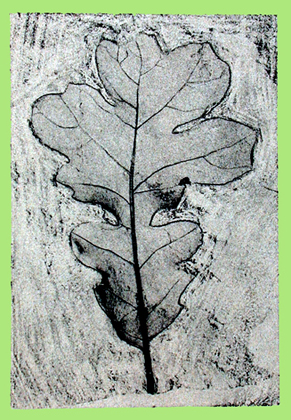

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--Premaxillary teeth from the extinct giant spike-toothed salmon (also called the sabertooth salmon) Oncorhynchus rastrosus, which lived roughly 12 to 5 million years ago during the mid Miocene to early Pliocene. The roughly 5 million year-old specimens came from a locality in the early Pliocene section of the upper Miocene to late Pliocene Mehrten Formation approximately 55 miles south of Angels Camp (turnoff point for the fossil plant bonanza in the High Sierra Nevada, Alpine County, California) in a transition zone between the Great Central Valley and the western Sierra Nevada foothills. Size-reference vertical bars in image are one inch long, by the way. Letters A, B, and F are left teeth--the remainder are right teeth. Estimated size for the giant spike-toothed salmon is six foot three inches long; probably it weighed in excess of 375 pounds. Photograph courtesy a specific scientific document. Right--Canid jaw material from the upper Miocene portion of the late middle through late Pliocene Mehrten Formation. These specimens are roughly 6 million years old. I modified the image from a freely available photograph, which unfortunately provided no identifying information. Bar scale is presumably one centimeter. Is is well established by vertebrate paleontologists, though, that as presently understood (2018) the Mehrten Formation yields four species of canids: two borophagines--the famous bone-crackers Borophagus parvus and B. secundus of probable hyena-like dietary behavior--and two canines (related to modern dogs--Eucyon davisi and Vulpes stenognathus). Photograph courtesy a specific scientific document. |

|

|

|

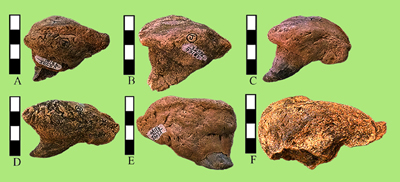

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--A mastodon tooth from the upper Miocene to lower Pliocene Mehrten Formation; genus-species is Mammut americanum, approximately 10 to five million years old. The specimen came from a locality discovered on private property in 2020 in the vicinity of Camanche Reservoir, western foothills of the Sierra Nevada, California. Photograph courtesy East Bay Municipal Utility District. Right--An undescribed (in the scientific literature) tapir jaw from the upper Miocene to lower Pliocene Mehrten Formation, approximately 10 to five million years old. The specimen came from a locality discovered on private property in 2020 in the vicinity of Camanche Reservoir, western foothills of the Sierra Nevada, California. Photograph courtesy East Bay Municipal Utility District. |

|

|

|

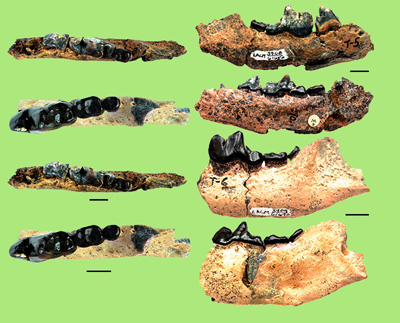

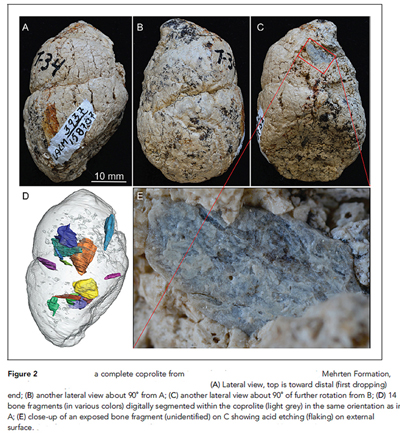

| Click on the image for a larger picture. Three viewing perspective of the same canid coprolite (petrified poop) from the upper Miocene Mehrten Formation. The specimen is roughly 6 million years old and probably came from a borophagine canid called Borphagus parvus, an extinct bone cracking dog of presumed hyena-like dietary preferences. Photograph courtesy a specific technical document. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|