|

When visiting Virginia City, western Nevada--the "Queen

of the Comstock"--take a special look around you at the

glorious Basin and Range scenery. It seems to sweep forever to

the east, beyond the horizon, in the heart of a great pinyon

pine-juniper woodland. The dominant shrub here is Basin sage,

with such regular subordinate associates as rabbitbrush, desert

peach, bitterbrush, and hairy horsebrush.

Now try to imagine what this land would have looked like

some 12 to 13 million years ago: The pinyon pine-juniper-sagebrush

botanic component is gone, no mountains, only hilly topography.

In place of thirsty dry washes, many crystalline lakes and sluggish

streams lie scattered eastward in the distance. To the immediate

west, the central to southern sector of the ancestral Sierra

Nevada is but a relatively low ridge approximately 3,000 feet

high and gives no apparent indication that its summits will continue

to rise, on average, many thousands of feet with the passing

of geologic time (the northern Sierra Nevada has of course stood

at roughly its present-day height since around 50 to 40 million

years ago). All around you, enveloping you, is a dense mixed

conifer forest of Douglas-fir, western white pine, ponderosa

pine, white fir, and magnificent giant sequoia. The overall scene,

in fact, is strikingly similar to the modern-day moist western

slopes of the Sierra Nevada in the vicinity of Calaveras Big

Trees State Park, some 23 miles northeast of Angels Camp, California--an

area that supports an inspiring giant sequoia forest community.

If such a vastly different character of the land seems

downright shocking---patently unbelievable in the main--the verifiable

proof its existence in the geologic past can be examined only

a moderate distance from the exciting Old West atmosphere of

Virginia City in western Nevada, where the internationally renowned

Comstock Lode yielded incalculable fortunes in silver and gold,

mainly from 1859 to the 1880s (when miners discovered at least

six individual, major bonanza bodies), with sporadic rich mineralization

encountered underground through the 1920s. Within a reasonable

driving distance of the famed silver mining camp lies a regional

badlands district where paleontologically productive exposures

of sedimentary rock yield the remains of numerous species of

fossil plants, insects, and even frogs--all dating from the late

middle Miocene, some 12.7 million years old.

This Virginia City-vicinity fossil site is an especially

rich one. In addition to the remains of insects, occasional frog

skeletons, and prolific microscopic diatoms, some 30 additional

species of macrofossil plants have also been identified from

the Virginia City/Comstock Lode area, including giant sequoia

and such dicotyledonous deciduous varieties as willow, birch,

alder and cottonwood, for example. Most of the fossil beds occur

in an often economically lucrative sedimentary material called

diatomite, a rock type composed almost entirely of diatoms, a

microscopic photosynthesizing single-celled algae that periodically

proliferated in ancestral west to central Nevada during middle

to late Miocene times, contributing myriads of their intricately

designed frustules to the accumulating geologic record. Indeed,

in the early 1900s, a commercial mining operation extracted high

grade diatomite from the vicinity of the fossil locality near

Virginia City, and shipped the processed product to New York

for use in the manufacture of a silver polish; and that leads

to the rather curious consideration that perhaps numerous individuals,

in possession of silver ornaments and utensils created from Comtock

Lode mineral extraction, might have polished their valuable metallic

objects with a product originally mined near Virginia City, as

well.

In addition to its value as an abrasive in polishes, diatomite

also finds use in several other commercial applications, including:

filters (in swimming pools, for exzample; also helps clarify

beer and wine); insulation material; as a whitener in paints;

toothpaste; as an absorbent for pet litter and industrial spills;

a silica additive to cement and numerous other compounds; and

a well-known natural insecticide (AKA, Diatomaceous Earth).

Geologist Vincent P. Gianella discovered the Virginia City-vicinity

fossil flora in 1935 during his detailed investigation of the

Comstock Lode in the neighboring Silver City region (a small

community situated approximately four miles south of Virginia

City). For a preliminary estimate of its geologic age, Gianella

turned his collection over to then noted paleobotanist Ralph

Chaney, who determined that the ancient botanic specimens were

most likely of early Pliocene age--a rather raw initial relative

geologic age evaluation that eventually proved inaccurate, but

it was a close paleobotanical call due to a few exotic old-world

deciduous plant species in the Comstock Lode-area flora. More

recent, definitive, radiometric age-dating techniques (radioactive

isotope analyses) on volcanic constituents within the local stratigraphic

section constrain the flora to around 12.7 million years old--or

late middle Miocene in geologic age.

For a more detailed analysis of the fossil flora, Chaney

gave the specimens to a colleague, Mary S. Leitch, who concluded

rather incisively that in order to accomplish the task much more

fossil material needed to be collected; unable to undertake the

necessary collecting expedition, Chaney and Leitch eventually

directed 29 year-old paleobotanist Daniel I. Axelrod to head

out into the field. In 1939, Axelrod spent several days gathering

additional fossil plants at the Comstock Lode/Virginia City locality.

Axelrod's larger fossil sampling so altered the overall

paleobotanical aspect of the collection originally studied that

a whole new approach to its scientific interpretation was now

in order. When Dr. Leitch informed Dr. Chaney that she could

not complete the project due to a conflict in professional priorities,

Axelrod happily took over the study, and over the next numerous

years, interspersed among other scientific research projects,

cumulatively amassed decades in assiduous elucubrations before

eventually publishing a superior paleobotanical monograph on

the Virginia City-vicinity fossil plant locality.

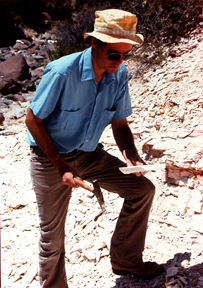

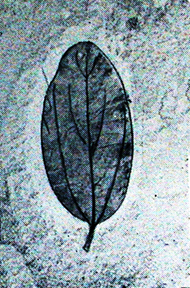

In preparation for his technical paleobotanical treatise,

Axelrod employed especially efficient excavating expertise in

the field to secure some 3,639 fossil plant specimens from the

Comstock Lode/Virginia City flora. He then determined through

methodical statistical analyses that the most common plants encountered

were leaves belonging to (1) Populus eotremuloides, the

Miocene analog of the living Black cottonwood (Populus trichocarpa)--followed

by, in decreasing order of relative abundance: (2) Betula

thor (leaves)--Paper birch, Betula papyrifera; (3)

Salix knowltoni (leaves), Lemmon's willow--Salix lemmonii;

(4) Populus washoensis (leaves), Bigtooth aspen--Populus

grandidentata; (5) Chamaecyparis linguaefolia

(leafy twigs and cones)--Lawson cypress, Chamaecyparis

lawsoniana; (6) Amelanchier alvordensis (leaves)--western

serviceberry, Amelanchier alnifolia; (7) Sequoiadendron

chaneyi (leafy twigs)--Giant sequoia, Sequoiadendron giganteum;

(8) Pinus wheeleri (fascicles and seeds)--Western white

pine Pinus monticola; (9) Abies concoloroides (cone

scales, (needles, seeds and leafy twigs)--white fir, Abies

concolor; (10) Populus pliotremuloides (leaves)--quaking

aspen, Populus tremuloides; (11) Salix owyheeana

(leaves)--coastal willow, Salix hookeriana; (12) Ceanothus

chaneyi (leaves)--Deer brush, Ceanothus integerrimus;

(13) Ceanothus leitchii (leaves)--Tobacco brush, Ceanothus

velutinus; (14) Rhododendron gianellana (leaves)--Western

azalea, Rhododendron occidentale; (15) Ribes stanfordianum

(leaves)--Flowering currant, Ribes sanguineum; (16) Pseudotsuga

sonomensis (leafy twigs, needles and seeds)--Douglas fir,

Pseudotsuga menziesii; (17) Pinus florissanti (cones

and needles)--Ponderosa pine, Pinus ponderosa; (18) Alnus

smithiana (cones)--Mountain alder, Alnus tenufolia;

(19) Castanopsis sonomensis (leaves)--Golden chinquapin,

Castanopsis chrysophylla; (20) Salix laevigatoides

(leaves)--Red willow, Salix laevigata; (21) Carya bendirei

(leaves)--Shagbark hickory, Carya ovata; (22) Quercus

simulata (leaves)--Chinese evergreen oak, Quercus myrsinaefolia;

(23) Mahonia reticulata (leaves)--Cascades oregon grape,

Mahonia nervosa; (24) Holodiscus idahoensis (leaves)--oceanspray,

Holodiscus microphyllus; (25) Prunus moragensis

(leaves)--Bitter cherry, Prunus emarginata; (26) Rhamnus

precalifornica (leaves)--California coffeeberry, Rhamnus

californica; (27) Arbutus matthesii (leaves)--Pacific

madrone, Arbutus menziesii; (28) Cupressus sp.

(leafy twigs)--a second species of cypress; (29) Tusga mertensiana

(seeds)--mountain hemlock; and (30) Pinus balfouroides

(cones)--Foxtail pine, Pinus balfouriana.

The fossil plant, insect, and amphibian (AKA, frog) material

is found exclusively in the sedimentary strata of a geologic

rock deposit called the Coal Valley Formation, dated at late

middle Miocene on the geologic time scale, approximately 12.7

million years old. Axelrod, for example, collected all of his

paleobotanic specimens from Member 3 of the Coal Valley Formation,

some 330 feet of pure white to creamy white well bedded diatomite,

often laminated, with occasional layers of yellow to brown andestic

tuffs and breccias roughly six inches to four feet thick.

Once at the specific site within a reasonable driving distance

of Virginia City and the fabulous Comstock Lode, hike into the

hills, looking especially for the brilliant white stratified

rocks--the diatomites (composed of diatoms, a microscopic photosynthesizing

single-celled algae) and associated fine-grained siliceous shales

which regionally underlie the diatom-rich deposits.

Axelrod's original primary fossil plant locality occurs

in a prominent exposure of diatomite roughly 15 feet thick and

about 30 feet long--obviously not an overly extensive area of

fossiliferous sediments, yet infrequent to moderately common

remains of deciduous and evergreen leaves occur here, in addition

to gymnospermous conifer seeds, leafy twigs, needles, fascicles,

cones, and cone scales. Use a geology pick/rock hammer to whack

out--read: carefully remove--the potential leaf-yielding rocks.

Should no evidence of a fossil appear on the exposed surface,

gently rap the diatomites along their bedding planes with the

blunt end of that same standard geology hammer. This procedure

will provide a greater opportunity to locate something extraordinary;

and please note, by way of a recommendation based on personal

experience--disabuse oneself entirely of utilizing one of those

wide blade roofer-type hammers, typically advocated by any number

of paleobonists for all plant-bearing sedimentary rocks. Maybe

such a roofer's "weapon" works well with classically

soft fissile shales, but the implement lacks punch, heft, the

necessary compact mass to efficiently cleave diatomites with

a single sure strike, a method that improves exponentially the

probability of discovering excellent paleontobotanical specimens.

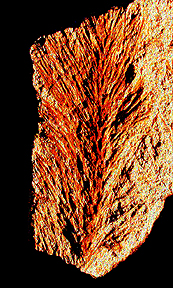

Sometimes the fossil leaves remain difficult to spot due

to the sun's glare on the bleached bone-white diatomite, so try

getting into the shade of a nearby juniper or pinyon pine for

a more comfortable examination of the specimens. The 12.7 million

year-old leaf impressions typically appear in shades of reddish

orange to pale brown. And while deciduous and evergreen leaves

might at first blush appear most conspicuously represented, watch

carefully for conifer seeds, needles, fascicles, leafy twigs,

cones and cone scales--other botanic specimens commonly observed

here.

Approximately two-tenths of a mile northeast of the main

fossil locality first investigated by Daniel I. Axelrod lies

an abandoned open pit diatomite mine. Excellent representative

samples of high grade, quality diatomite can be collected here.

The most common diatom specimens from the Virginia City-vicinity

locality consist of Actincyclus cedrus and Melosira

granulata; under powers of moderate magnification (through

the implementation of microscopy), the diatom species fascinatingly

resemble miniature discs and boxcars linked together in short

chains, respectively. Paleoecologically speaking, a prevalence

of Actinocyclus cedrus and Melosira granulata diatoms

from the late middle Miocene Coal Valley Formation here signifies

that the lacustrine hydrologic system within which they propagated

probably displayed the following characteristics: moderate eutrophy;

a relatively shallow depth; warm monomictic, with regularly cyclic

circulatory mixing during winter; slight alkalinity, with a pH

level that would have registered close to 8.0; a high silica

content; and winter temperatures that never dropped below 39.2

degrees Fahrenheit.

Geochemical conditions required to stimulate a proliferation

of diatoms necessary to produce economically valuable deposits

of diatomite include: significant concentrations of silica, usually

supplied by volcanic activity; a pH that generally ranges from

6 to 8; high potassium and magnesium content, in relative relatonship

to low ratios of sodium and calcium; loads of the element boron;

and high proportions of phosphate and nitrate, generally provided

by upwelling waters in the lacustrine system.

While at the diatomite mine, examine the strata exposed

there for additional fossil leaves, needles, seeds and twigs--plus,

rare excellently preserved frog skeletons. Although not as plentiful

here, the macro-paleobotanical remains are sometimes present

within several layers of the less-pure, lower-grade diatomites,

the sediments with an off-white to brownish tone. The specific

species of fossil frog found in the late middle Miocene Coal

Valley Formation is called Rana johnsoni, an amphibian

that shows morphological relationships to two modern frogs. One

is Rana pipiens, the Northern leopard frog, now native

to parts of Canada southward through Kentucky and westward to

New Mexico (southernmost occurrence is in Panama, Central America,

though this is possibly an undescribed species); it prefers grasslands,

lakeshores, and marshes. The other resemblance is to the California

Red-legged frog Rana draytoni (historically endemic to

California's western Sierra Nevada foothills and coastal areas,

southward to the northern Baja peninsula, though for all intents

and purposes it's been extirpated from Los Angeles south to the

Baja border); in optimal natural habitat, the California Red-legged

frog likes ponds, streams, marshes, and springs, preferably with

deep pools that contain abundant overhanging willows and a fringe

of cattails.

Of course, it is well to remember that one must not collect

vertebrate fossils on public lands without first securing a special

use permit from the BLM (Bureau of Land Management), a permit

issued solely to individuals with a minimum B.S. degree from

an accredited university who either represent an officially recognized

museum, or seek to undertake scientific research projects that

can be fully verified as authentic by the petitioned authorities.

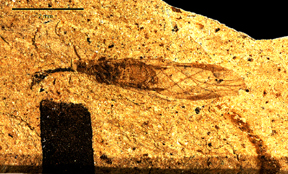

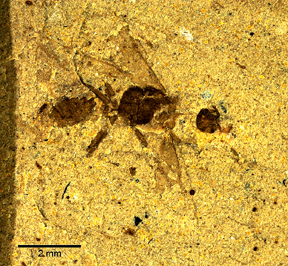

Another fossil type represented in the local late middle

Miocene Coal Valley Formation near Virginia City, Nevada, is

the arthropod--specifically, insects. They occur in detrital,

non-diatomaceous strata slightly older than the fossil plants,

but they're still in the neighborhood of approximately 12.7 million

years old. The matrix upon which they're preserved is quite reminiscent

of the classic paper shale deposits at world-famous Fossil Valley,

Great Basin Desert, Nevada (now a federally protected region,

completely off limits to unauthorized collectors). Here, though,

the brownish to tan shale beds that exhibit cleavable planes

of deposition no thicker than a proverbial sheet of paper are

nowhere near as extensively exposed as those featured at Fossil

Valley, and the insect preservations, while sometimes superbly

striking, remain far less commonly encountered, as well. Unfortunate,

that--most obviously--but due to the wholly natural vagaries

of variable fossil abundance in the geologic record, that's exactly

what one expects to experience in the field from time to time.

Paleoentomologic specimens thus far identified from the Comstock

Lode/Virginia City fossil district disclose dominantly diminutive

dipteran varieties--that is to say, a paleo-fauna comprised of

flies, gnats and midges, mainly, with a few hymenoptera also

present. Examples of paleobotanical preservations also occur

in the insect-bearing shales--on occasion, for example, one comes

across excellently carbonized remains of winged conifer seeds

and needles.

Based on the geological and paleobotanical evidence, the

present-day Comestock Lode/Virginia City-area paleontologic locality

indeed appeared dramatically different some 12.7 million years

ago. For example, the diatomites within which the fossil leaves

occur were laid down in a small lake basin at an altitude probably

no higher than 2,500 feet (though regional summits would have

ranged higher, of course), near the western terminus of the so-called

Miocene-age Nevadaplano that gradually increased in elevation

eastward toward the Rocky Mountains. By about 17 million years

ago, extensional tectonic forces had already begun to pry apart

portions of the nascent Great Basin, creating an emergent landscape

that adumbrated modern Nevada geography; based on geophysical

studies in Nevada's Pine Nut Range, westernmost ancestral Nevada

(including the Virginia City area), still part of the once vast

Nevadaplano, began to develop Great Basin-style geography through

extensional strains at roughly 6.8 million years ago. Bordering

the lake was a dominantly deciduous woodland consisting of Black

cottonwood, Paper birch, Bigtooth aspen, and three kinds of willows

(Lemmon's willow, Red willow, and coastal willow). A mixed conifer/Big

tree forest reached the shoreline along well-drained gravelly

stream banks that penetrated the riparian association. In addition

to Lawson cypress and giant sequoia, the primary forest species

present, there were also numerous examples of Douglas-fir, western

western white pine, ponderosa pine, white fir, mountain hemlock,

Foxtail pine, a second species of cypress, Golden chinquapin,

Shagbark hickory, Pacific madrone, and Chinese evergreen oak.

Included in the forest community were such understory shrubs

as bitter cherry, serviceberry, Deer brush, Flowering currant,

Western azalea, Cascades oregon grape, oceanspray, and Mountain

alder. Modern-day botanic associations that most closely resemble

the plant types preserved in the late middle Miocene Coal Valley

Formation near Virginia City can be explored in such California

areas as: Calaveras Big Trees State Park; Giant Forest in Sequoia

National Park; General Grant Grove, Kings Canyon National Park;

Sequoia Lake in Fresno County; and the south fork of the Sacramento

River, southwest of Mount Shasta.

Not only did the landscape support a greater variety of

vegetation than the present-day Great Basin terrain, but the

climate of those ancient late middle Miocene times was also corresondingly

more temperate. Today, rainfall in the region is about 15 inches

yearly; yet, the known requirements of living members of the

fossil flora show that at least 20 inches more rain fell approximately

12 to 13 million years ago, or roughly 35 inches annually. The

Miocene rains were distributed as both winter and summer showers--in

other words, pretty much year-round--whereas today's Mediterranean-style

meteorological patterns, in areas of California's western Sierra

Nevada foothills that support giant sequoias and other plants

either identical or at least very similar to those observed in

the fossil flora, produce effective rain and snow only from winter

through spring; summers there typically provide but a paucity

of precipitation, creating a somewhat less mesic environment

than what existed in the vicinity of Virginia City during late

middle Miocene times. That difference in seasonal rainfall eliminated

from modern Sierran sequoia habitats all botanic species in the

fossil flora that require regular, substantial summer showers:

paper birch; Chinese evergreen oak; Lawson Cypress; a second

species of cypress (Cupressus sp.); mountain hemlock;

and Shagbark hickory. At the fossil site today, virtually every

ounce of effective precipitation arrives as snow during the winter.

Probably the Miocene frost-free season was as long as seven months--while

today it's closer to four. In general, it appears that late middle

Miocene winters were much warmer and summertimes cooler than

those observed during recent times.

Today, Virginia City lies on the western edge of the arid

Great Basin. As a physiographic province, this mountainous land

dominates all of Nevada, in addition to portions of eastern California,

southeastern Oregon, southern Idaho, and western Utah. It is

a region characterized by three archetypical botanic types--sagebrush,

juniper, and pinyon pine. Yet, the Comstock Lode-vicinity fossil

plants prove that 12.7 million years ago a diverse deciduous

and evergreen dicotyledon community mingled with a rich mixed

conifer forest amid a moist environment quite similar to a giant

sequoia/Big tree grove in present-day California.

At that distant Miocene time, the southern to central Sierra

Nevada district was but a relatively minor ridge, perhaps 3,000

feet high, and nourishing rainstorms from the Pacific had free

run across ancestral west-central Nevada. Vegetation was lush,

the climate temperate--a rain-saturated humid scene reminiscent

of today's western foothills of the Sierra Nevada and a tributary

of the Sacramento River near Mount Shasta.

Eventually, about three million years ago, the central

to southern Sierra began to rise in earnest, reaching skyward,

thrust upwards thousands of feet by potent tectonic forces, until

the now exposed western slopes captured most of the eastward-driven

precipitation. In ancient Nevada, the once extensive forests

of Big trees died back, shrinking, finding their final refuge

in isolated, environmentally favorable localities in the western

Sierran foothills. Aridity reigned. The numerous lakes and streams

dried up, vanished, leaving behind within secret sedimentary

layers their wonderful evidence of a prehistoric age, the fossil

plants, insects and frogs waiting in the rocks, waiting for us

to learn of what once existed in this part of western Nevada

so many millions of years ago.

|